ENI as a Geopolitical Actor: Italy’s Energy Diplomacy in the Mediterranean

By Luca Guerzoni

Introduction

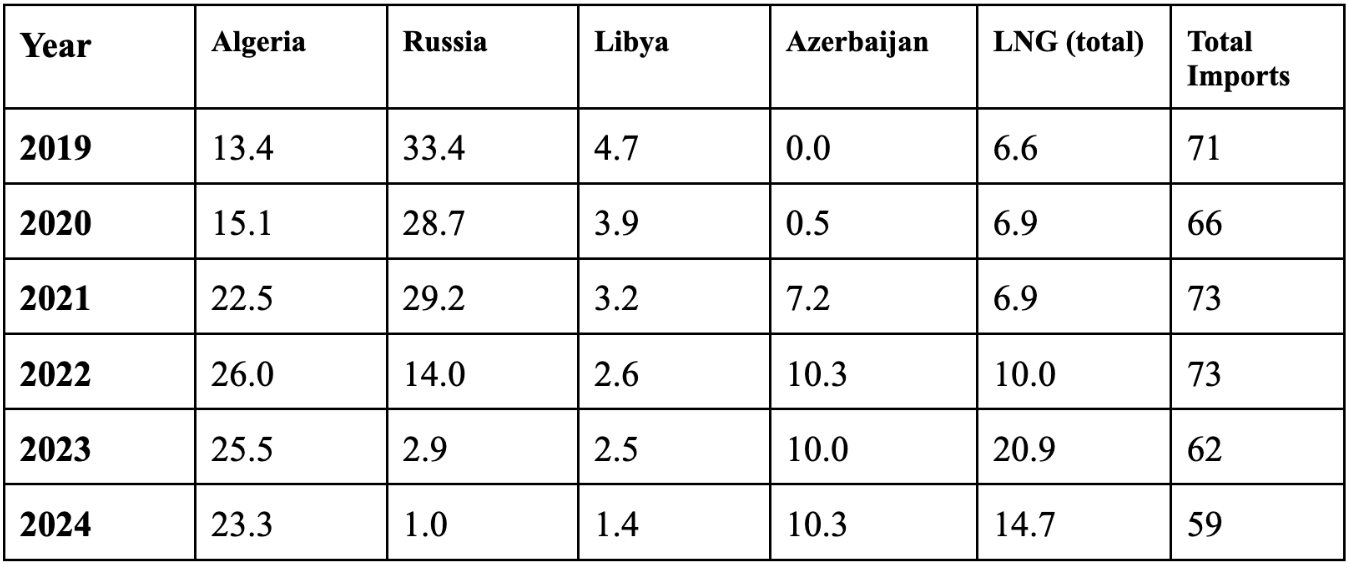

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 prompted a drastic shift in Europe’s energy landscape. Italy, which used to be reliant on Russian gas for 40% of its total gas imports before the war, reoriented its energy strategy to find alternative sources of gas to move away from Russian gas. In this change of strategy, Italy emerged as a pivotal getaway for alternative energy corridors linking Europe to North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. Italy’s geographical location in the Central Mediterranean, at the crossroads of an extensive network of pipelines and maritime routes, and its historical and cultural relationships with Mediterranean states make it an indispensable bridge between Europe’s energy needs and its Southern suppliers.

Natural Gas Imports by Source (bcm) - ARERA

Capitalizing on this moment is ENI (Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi), which is Italy’s partially state-owned energy company and one of the most geographically expansive multinationals in the region. ENI is a unique “hybrid” actor, since its ownership structure closely ties it with the Italian state, which has a total share of 31.825% in the company, while its global operations, technical autonomy, and long history of independent deal-making have made it function not just as an extension of Italian foreign policy, but rather as a geopolitical actor on its own right. In fact, ENI operates as a business-driven geopolitical actor whose initiatives often align with Italian state interests, even though are not reducible to it. In the post-2022 landscape, ENI’s pursuit of commercial opportunity, its risk diversification, and its energy security has frequently complemented Italy’s diplomatic agenda and Europe’s broader diversification efforts, even as ENI maintains a significant strategic autonomy in shaping the Mediterranean energy order.

Historical Background

ENI dates its origin back to the immediate postwar years, when Enrico Mattei, a wartime partisan commander and entrepreneur, was appointed to dismantle what remained of AGIP, which was a discredited Fascist-era state oil company ready to be liquidated. The discovery of extensive methane reserves in the Po Valley, near Cortemaggiore field in 1949, overturned the assumptions that have justified AGIP’s liquidation, which included that Italy had no meaningful hydrocarbons of its own and therefore there was no need for a state energy enterprise. In addition to that, the discovery also revealed that Italy possessed a domestic energy resource capable of transforming its industrial future. Giving his time spent fighting in the Resistenza, which was the armed Insurgency against the Fascist regime first, and then the Germans during the Italian civil war 1943-46, Enrico Mattei had witnessed how foreign dependence had made Italy strategically vulnerable, and therefore he was aware that the post-war reconstruction required infrastructural self-reliance, particularly in energy. Instead of liquidating AGIP, Mattei repurposed it to construct distribution networks in order to supply the newly discovered methane to an industrial sector still damaged by the war. These efforts culminated in the creation of ENI in 1953, which consolidated exploration, refining and pipeline infrastructure into a vertically integrated state conglomerate designed to secure national autonomy. The foundation of ENI provided Mattei with an institutional base to advance his doctrine of energy sovereignty, which consisted in establishing autonomy from the ‘Seven Sisters’ (The seven oil companies that dominated the energy market from 1940s to the 1970s) and in capitalizing on the wave of decolonization in several energy-rich countries by establishing partnerships with them. In fact, Mattei, who rejected the traditional concession system and the oligopolistic control of the Anglo-American majors on the pricing, noticed a window of opportunity to advance more generous profit-sharing formulas with oil-producing countries and to assume greater exploration risk in exchange for long-term access. This strategy and the success that followed became both a driver of Italy’s economic miracle and the core of ENI’s geopolitical identity. ENI’s Middle Eastern operations between 1955 and 1962 shows how Mattei proposed contracts that broke with the standard 50-50 divisions and offered infrastructure and technical assistance. This contributed to portray the image of ENI as an equal partner rather than a neo-colonial operator. This strategy followed a very specific political agenda: by privileging decolonizing states and “Third World” actors, Mattei pursued what Belloni calls a “non-colonialist” approach, which was publicly described in ENI’s in-house magazine Il Gatto Selvatico as solidarity with people emerging from European rule and as an alternative to Western monopolies. This strategy of combined autonomy from the oil majors, diversification of supply from a single bloc, and the partnership with newly independent states gave Italy a big margin of maneuver in energy geopolitics of the 1950s. An example of how Mattei’s modus operandi in business and his rejection of Western imperialism influenced Italy’s foreign policy was the convergence between Mattei and the Italian state, evident in Italy’s support for Algerian independence and its political distancing from Britain and France during the 1956 Suez Crisis. By challenging British and French energy and colonial interests head on, Mattei’s actions ensured ENI became a deeply suspect and detested organisation in both Paris and London, thereby placing Italy in direct competition with the European Western powers for influence, resources, and autonomy in the Mediterranean. As ENI expanded into Egypt, Iran, Libya, and revolutionary Algeria, it developed a “business-first geopolitics” in which contracts and pipelines functioned as instruments of influence that often preceded or, at times, reshaped diplomatic alignments, making Italy to carve out an autonomous Mediterranean role within the polarization of the Cold War. The unusual favorability of these long-term contracts and deals was functional in depicting Italy's image as a non-imperial interlocutor and in embedding Italy in the political economies of the MENA producers. This produced a dual structure, in which ENI became both a national asset and a semi-independent geopolitical actor. Historian Eleonora Belloni described this as a “parallel foreign policy”, as it was mostly shaped by Mattei’s personal networks and institutional worldview. Contemporarily, the Meloni government has presented in 2023-24 the “Mattei Plan” for Africa, mobilizing the legacy of Enrico Mattei and his business strategy. Analysis by SWP Berlin on the plan shows a lot of Mattei’s core logics such as presenting Italy as a partner and promising co-development projects rather than mere resource extraction. The Plan relies heavily on ENI’s operational presence and shows continuity in Mattei’s methodology. In fact, energy deals, gas corridors and renewables projects in North and sub-Saharan Africa are framed as simultaneously economic and geopolitical tools and are meant to make Italy an energy hub between producer states and the European market.

ENI in North Africa: The Core of Italy’s Energy Strategy

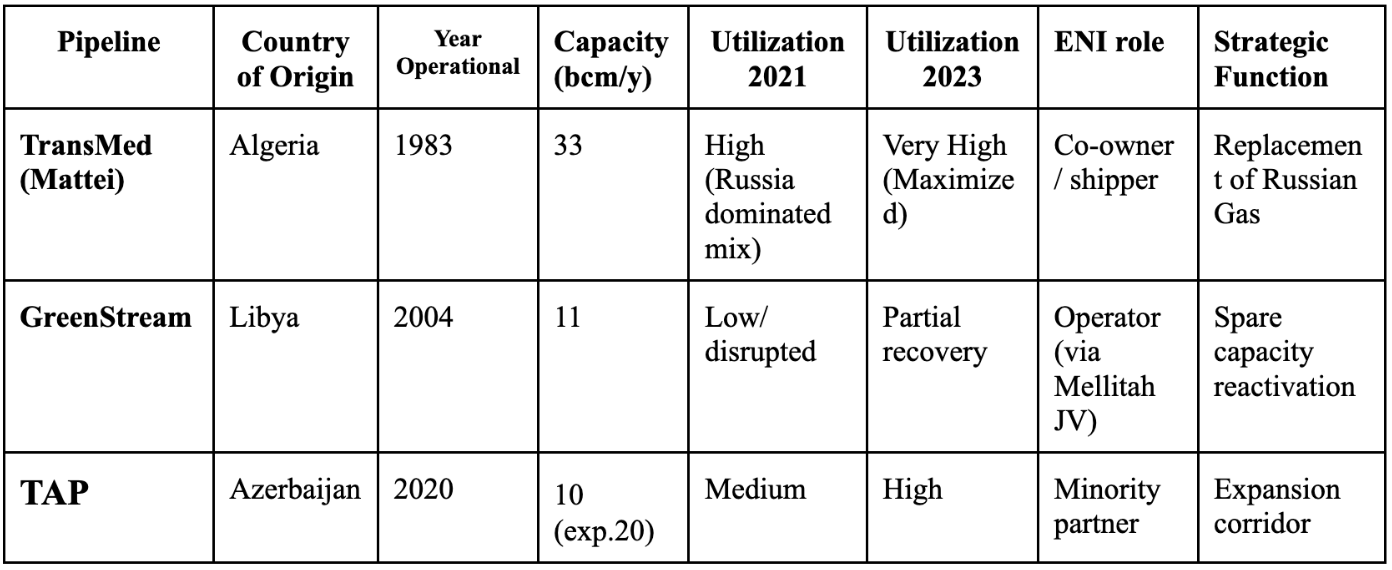

Capacity figures are technical maxima. Utilization levels are expressed qualitatively based on reported throughput trends before and after 2022 (ENTSOG, Snam, operator disclosures)

The war in Ukraine and Europe’s break from Russian gas made Italy reinvent its energy strategy. Rome has made North Africa – particularly Algeria, Libya, and Egypt – the foundation of its diversification plan. North African gas pipelines now form Italy’s vital energetic lifelines, with ENI solidifying Italy’s role as Europe's southern gas hub. In each key country, ENI’s initiatives, which range from boosting pipeline flows to discovering supergiant fields, underpin Italy’s influence and geoimperative strategy.

I. Algeria

Pipelines between Italy and Algeria

Algeria has always been historically one of Italy’s key gas suppliers. Italy shares with this North African country a deeply rooted relationship which finds its main expression in the energy sector, where ENI’s partnership with Algeria’s national oil company, Sonatrach, has become the institutional backbone of bilateral cooperation. The depth of this relationship is symbolically reflected in Algiers itself, where a statue of Enrico Mattei commemorates his support for Algerian independence and Italy’s early political alignment with the Algerian cause. Building on this foundation of trust, Italy and Algeria deepened their energy ties through large-scale infrastructure projects, most notably the TransMed pipeline (also known as the Mattei pipeline) which today anchors Algeria’s central role in Italy’s energy diversification strategy. In fact, The “Mattei pipeline”, which runs from Algeria’s Hassi R-mel gas fields across Tunisia to Sicily, has become Italy’s primary artery in the post-Ukraine landscape. In May 2022, Italy signed a deal with Algeria’s Sonatrach to boost the “Mattei pipeline” throughput from 21 bcm annually to 30 bcm by end-2023. By 2023, Algeria officially replaced Russia as Italy’s largest gas supplier, now providing 36% of Italy’s total gas imports. In 2022, ENI signed a $1.5 billion contract with Sonatrach to jointly explore and develop the Zemoul El Kbar field in the Berkine basin, as well as the green hydrogen pilot project in Bir Rebaa North (BRN). Also in 2023, during Italian PM Giorgia Meloni’s visit to Algiers, ENI and Sonatrach signed two memorandums of understanding that aimed at increasing export capacity from Algeria to Italy and to jointly rescue greenhouse gas and methane emissions. This included a plan to optimize the TransMed throughput and even to evaluate the construction of the GALSI pipeline project, which would connect Algeria to Sardinia. This memorandum shows a mutual commitment to historical energy ties between the two countries and to future long term partnership, even in the field of energy transition. Furthermore, in July 2025, ENI and Sonatrach signed a $1.3 billion-worth deal that consist in the a 30-year development contract, with an initial exploration phase of seven years, to explore and develop hydrocarbon fields in the Zemourt El Kbar area, de facto locking Algeria as the future of Italy’s diversification strategy in the long term.

Geopolitically, this partnership has become the cornerstone of Italy’s “Mattei Plan for Africa”, which anchors Italy as Europe’s energy bridge to North Africa. In addition to that, Italy was able to perfectly diversify its gas imports from Russia and advance its influence in North Africa. Algiers gained a reliable EU market and increased its diplomatic leverage, reducing reliance on troubled ties with France, Morocco, and Spain. Future projects such as the GALSI pipeline project and joint efforts to reduce methane emissions, shows how this partnership is also evolving beyond hydrocarbons, providing a platform for future green energy cooperation.

II. Libya

GreenStream pipeline and Structures A&E, Mellitah Oil & Gas BV

In Libya, ENI has been a dominant actor since 1959, operating oil and gas fields in partnership with Libya’s NOC, a position that was politically consolidated with the 2008 Italy–Libya Treaty of Friendship signed by Silvio Berlusconi and Muammar Gaddafi, which envisioned Libya as Italy’s principal supplier of oil and gas. A result of this was the creation of the Mellitah Oil & Gas, a joint venture between ENI and NOC, which consisted of the joint management of the Wafa onshore field and the two offshore fields of Bahr Essalam and Bouri, and the construction of the GreenStream pipeline, connecting Mellitah and Gela. This partnership was halted by the breakout of the uprisings against Gheddafi. This led to the collapse in Libyan energy exports, with oil production falling from around 1.6 million barrels per day to below 300,000, while gas flows through GreenStream dropped from roughly 9–10 bcm annually to near zero. This forced Italy to abandon this strategy and pivot back toward increased reliance on Russian energy supplies. During the conflict, while most foreign companies left, ENI remained, becoming the pillar of Italy’s presence in its former colony. This made Italy’s Libya policy, which had the priority of migration control and energy security, increasingly reliant on ENI’s operational logic. As a result of this, Italy’s position in the country shifted from being a privileged partner with a unified Libyan state to becoming a more pragmatic, energy and security-oriented actor, following a policy revolved around the dialogue with all the warring sides (Tripoli’s Government of National Accord (GNA) and Tobruk-based Libyan National Army (LNA)), migration control, and the protection of ENI assets in the country. In January 2023, ENI and NOC signed a $8 billion agreement, which was Libya’;s first major energy deal in decades, to develop two huge offshore gas fields, known as Structure A and Structure E, which combined reserves mount to 6 tcf.

The project will produce up to 750 mcf per day (8 bcm per year) of gas for Libya’s domestic market and export to Europe. The deal also allows ENI to resume its offshore exploration and drilling in Area D northwest of the Libyan coast and includes the construction of a Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) facility in Mellitah complex to reduce emissions. All of this is expected to increase the throughput in the GreenStream pipeline, which has unused capacity of about 8 bcm/year. The deal also shows Italy’s commitment to Libya’s stability since the deal is expected to generate $13 billion in revenues for Tripoli, underscoring that it also aims to boost Libya’s economy. Italy has capitalized on ENI’s unique position of influence in the Libyan energy sector to reassert its influence, particularly in a time where rival powers (France, Russia, Turkey) exploit the civil war’s divisions. Italy, alongside Algeria and Turkey, officially supports Libya’s UN-recognized government in Tripoli, also because the majority of ENI’s oil and gas assets are located in the Western part of the country controlled by the Turkish-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) and their militias. Italy has also engaged in diplomatic dialogue with General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) and the House of Representatives (HoR) in order to manage migration fluxes and to support ENI’s primary interest in the East, which is preserving the unity and the authority of Libya’s National Oil Corporation (NOC), which is formally headquartered in Tripoli but it is heavily affected by eastern actors (HoR/LNA) who have several times tried to assert control over oil revenues. Taken together, Italy’s Libya policy illustrates a relationship of reciprocal capitalization: Rome has leveraged ENI’s entrenched operational presence to advance national priorities such as migration control and energy security, while ENI, acting as a commercially driven actor, has in turn benefited from Italy’s diplomatic engagement with rival Libyan authorities to secure exploration opportunities and preserve the unity of the NOC, revealing a dense interdependence in which business and state interests reinforce one another when their strategic objectives converge.

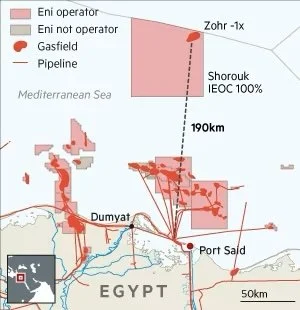

III. Egypt

ENI has been operating in Egypt since 1954, even though the biggest game changer was the discovery of Zohr in 2015, which is the largest gas field offshore in the Mediterranean, holding an estimate of 30 tcf. ENI discovered Zohr by using HPC supercomputers and proprietary algorithms that processed huge volumes of 3D seismic data and detected Zohr’s massive carbonate reservoir. ENI fast-tracked Zohr’s development and achieved first gas by late 2017. Zohr’s impact on Egypt was transformational: by 2018, the field’s increased output helped Egypt shift from natural gas importer to net exporter. Domestic shortages and blackouts became less frequent across the country, making the country de facto self-sufficient and by 2019, a net exporter of LNG. In addition to being the operator of Zohr, ENI is also the co-owner (50%) of the Damietta LNG facility, an important LNG terminal that Egypt uses for its LNG exports. ENI has helped Egypt to strike the 2019 deal with Israel that will make Egypt import 85 bcm of Israeli gas over 15 years via a reversal of the old Egypt-Israel pipeline. Meanwhile, in 2022 ENI’s joint licensed exploration with Total yielded the discoveries of Cronos-1 and Zeus-1, two offshore fields of an estimated 3 tcf of gas off the coast of Cyprus. In February 2025, Egypt and Cyprus signed an agreement to pipe gas from ENI’s Cronos field to Egypt’s Zohr facilities of liquefactions and re-export it to Europe. This plan leverages ENI’s infrastructure in Egypt (Zohr processing plant and Damietta LNG terminal) to unlock Cypriot gas for EU markets. Another Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2025 will route gas from Cyprus’s Aphrodite field, which is operated by Chevron, to Egypt as well. ENI has pledged to invest $8 billion over 2025-2030 to expand Egyptian oil and gas output and integrate with the regional hub concept. The strategy is simple: emphasizing short-cycled projects and field revitalization to sustain field production while maximizing the use of existing pipelines and LNG plants for efficiency. ENI currently produces about 40% of Egypt’s total gas and its work in the country is beneficial for both Italy and Egypt. Egypt became a net exporter of gas and a regional energy hub, while Italy receives some of Egypt’s LNG exports and ENI’s integration of Mediterranean gas does bolster Europe’s supply diversity.

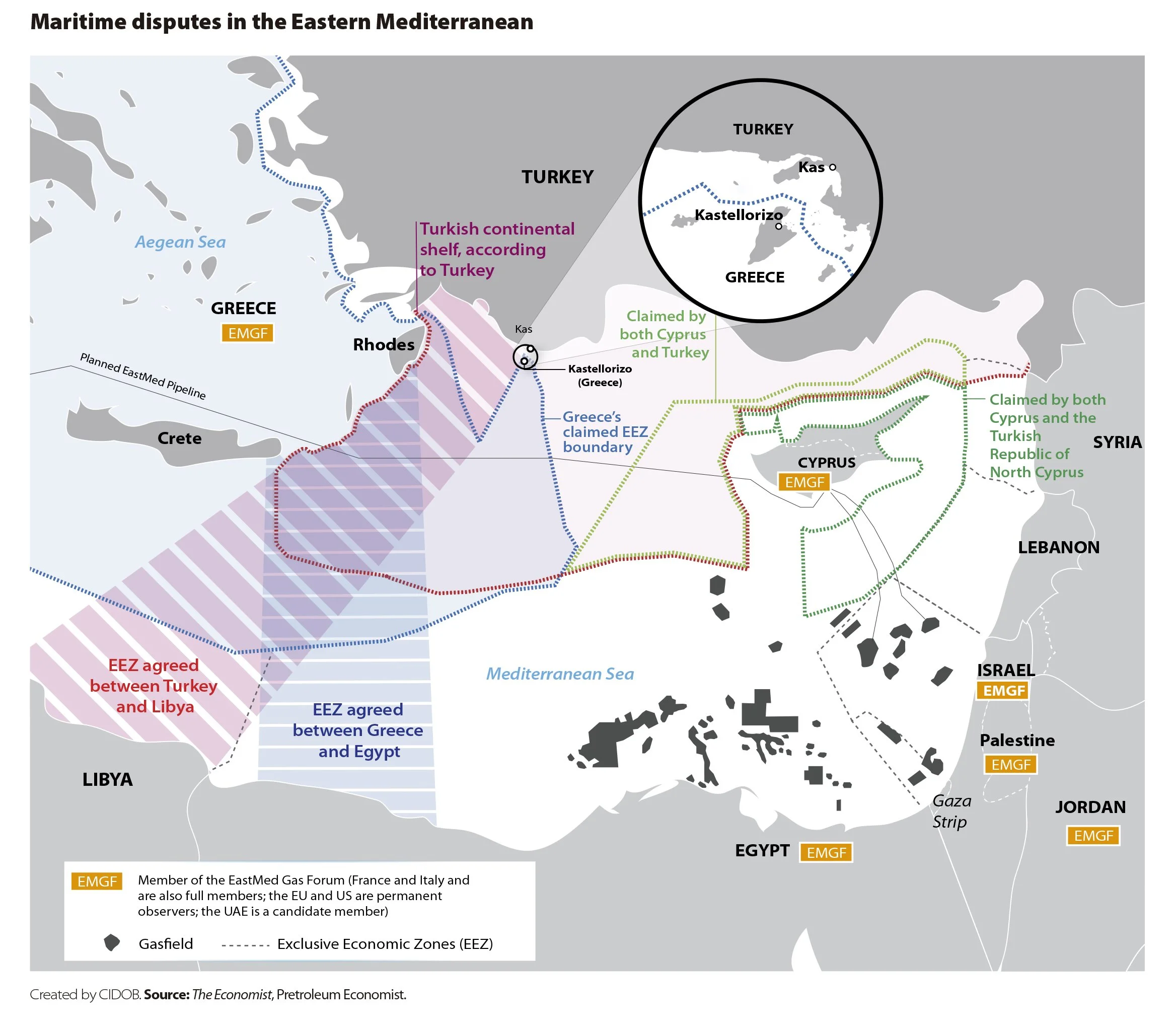

The Eastern Mediterranean: Cooperation, Competition, and Confrontation

I. Offshore Exploration

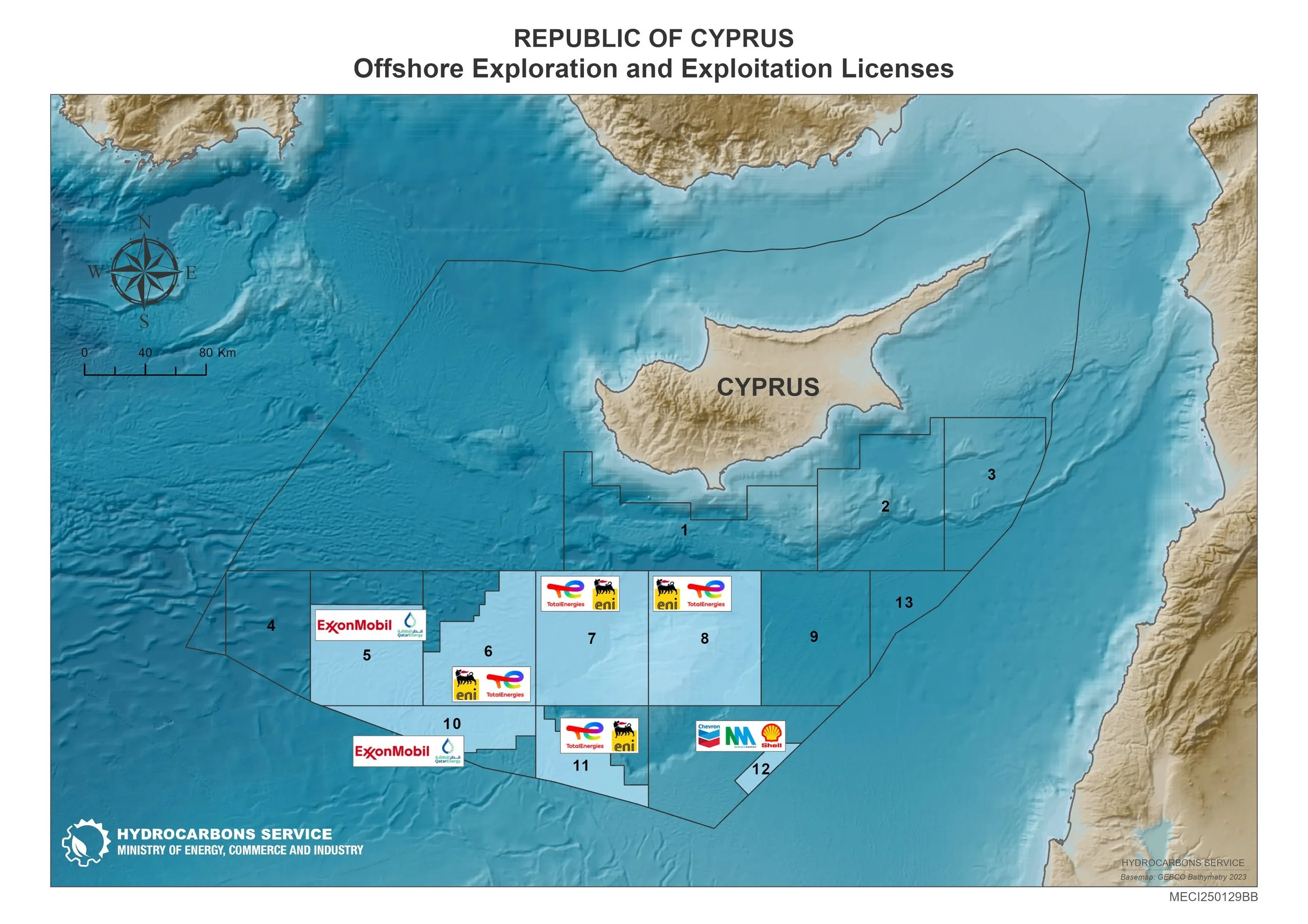

The map above shows the disputed Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) around Cyprus and the Levant, as well as the major gas fields. The overlapping claims affect ENI’s regional operations, given that the firm has obtained significant stakes in Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt, positioning itself at the center of the eastern mediterranean gas rush over the past decade.

In Cyprus, ENI is a leading explorer since it has multiple holding interests in Blocks 2,3,6, and 8. In 2018, the ENI/Total partnership discovered the Calypso prospect in Block 6, de facto extending ENI’s Eastern Mediterranean gas frontier beyond Egypt. Block 6 witnessed another ُENI’s discovery of the Kronos-1 well. Although Cyprus has seen three sizable finds (Aphrodite, Calypso, Kronos), none of these gas basins are producing. ENI’s discoveries remain untapped pending development plans. One of the main reasons for such delay is that Block 6 lies on the fringe of a zone claimed by Turkey as part of its continental shelf. In fact, Turkey claims that Greek Cypriots have no jurisdiction to drill without a Cyprus settlement.

Offshore licensing map for Cyprus (Eastern Mediterranean) showing blocks and their operators/partners. Eni (yellow dog logo) and TotalEnergies (red/white logo) jointly hold several blocks

ENI began operating in Israel in late 2022, following a US-brokered Israel-Lebanon maritime boundary deal. Since the deal was made, ENI now holds 40% stake in Lebanon’s offshore Block 9. In October 2023, Israel awarded a consortium of three companies (including ENI) a new exploration license west of the Leviathan field, de facto moving ENI into Israel’s gas future. ENI’s entry comes as Israel seeks more gas for export and regional export routes to Europe. Given the high costs and the geopolitical volatility of the region, ENI and its regional partners have prioritized shared infrastructure solutions. One example is the plan to tie Cypriot gas into Egypt’s existing LNG plants. In February 2025, ENI signed a landmark agreement with Egypt and Cyprus to develop a pipeline from Cyprus’s Block 6 (ENI’s Cronos/Calypso area) to Egypt’s coast, allowing Cypriot gas to be liquefied at Egypt’s Damietta LNG terminal and shipped to European markets. ENI hailed this as a “concrete milestone” toward an East Med gas hub leveraging Egypt’s facilities. Even earlier, Egypt approved a similar pipeline from the Aphrodite field (Cyprus’s first discovery, operated by Noble/Chevron) to an LNG plant in Egypt, a project that also required Israeli-Cypriot coordination, since Aphrodite extends partly into Israel’s EEZ. Meanwhile, Israel lacks its own LNG terminals and therefore began exporting gas to Egypt in 2020 via a repurposed undersea pipeline so that Israeli gas can be liquefied at Egypt’s Idku and Damietta LNG facilities for re-export to Europe. All of this shows a pragmatic trend: countries and companies are cooperating across borders to monetize gas quickly using shared pipelines and plants, rather than wait on complex new pipelines to Europe, such as the the EastMed Pipeline from Israel/Cyprus to Greece and Italy which won political support as an EU “Project of Common Interest,” but faces financing doubts and remains only on paper. ENI and Italy have chosen the strategy of making Egypt a regional hub by linking Eastern Mediterranean gas fields to Egypt’s energy infrastructures.

II. Turkey and Maritime Tensions

In recent years, Turkey has adopted the Mavi Vatan (“Blue Homeland”) doctrine, a strategic framework that seeks to assert expansive Turkish maritime sovereignty across the Eastern Mediterranean, Aegean, and Black Seas, explicitly rejecting established EEZ delimitations under UNCLOS and challenging the maritime claims of Greece, Cyprus, and their partners as part of a broader effort to project regional power at sea. This increased Turkish assertiveness in the Eastern Mediterranean has put Italian interest on a tightrope between EU solidarity, with Greek and Cypriot partners, and NATO alliance politics, with Turkey. Turkish maritime ambitions have led to a series of confrontations. In February 2018, ENI’s contracted drillship Saipem 12000 was en route to drill an exploration well in Cyprus’s Block 3 when it was intercepted by Turkish warships. The Turkish navy then forced the Italian-operated rig to withdraw. This sparked condemnation from Brussels and Nicosia, while ENI’s CEO, Claudio Descalzi, noted that the crisis was “not under our control”, leaving it to Rome to negotiate a solution. Angered at being excluded from regional gas development, Turkey began dispatching its own drillships, accompanied by naval escorts, into contested Eastern Med waters. In 2020, the Yavuz drillship targeted part of ENI’s Block 6, but claimed by the Turkish Cypriot. These “rogue” drilling incursions prompted the EU to condemn Turkey’s “illegal drilling” and impose sanctions on Turkish state oil executives. These maritime tensions have placed ENI and Italy in a difficult position, stuck between a rock of EU solidarity and a hard place of self-interest obligations. Indeed, while formally supporting the EU's position that Turkey must respect Greek and Cypriot EEZs, also backing EU statements, limited sanctions, and occasionally signaling support through naval participation, Rome has simultaneously avoided direct confrontation with Ankara-a key NATO partner central to Italian interests in Libya and migration management. This balancing act, embodied in Italy's preference for mediation and de-escalation rather than alignment with France's more confrontational stance, demonstrates how each naval incident has become a test of Italy's ability to defend legal and energy interests without destabilizing broader alliance politics. These dynamics put together show how ENI and the Italian state worked in tandem during the crisis, how corporate energy interests and national diplomacy mutually reinforced one another as Italy sought to protect its strategic position in the Eastern Mediterranean without sparking open confrontation.

III. Regional Governance and the EMGF

Against this backdrop of growing maritime uncertainties, Italy, together with ENI, has placed political credibility in the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) in line with Italy's wider energy diversification policy following Ukraine, with a view to lessening reliance on gas imported from Russia. Established in 2019 and formally launched in 2020, EMGF is based in Cairo, and membership involves Cyprus, Greece, Egypt, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and Palestinian Authority, with both France as a member and the EU and United States as observers. The initial and continued engagement of Italy in the EMGF signals a policy effort on Italy's part to achieve other gas sources via cooperative mechanisms, with ENI's strong presence in Egypt, Cyprus, and Israel making this company one of the major players in gas development and implementation schemes such as Egyptian LNG infrastructure for monetizing Eastern Mediterranean gas for consumption in Europe, although effectiveness in practice is currently impeded by Turkish absence, which contributes to broader divisions in international politics, making it impossible for EMGF to implement solutions in pressing maritime issues. Through this all, ENI and the Italian state have marched in lockstep, with ENI functioning as the executive arm of Italy’s post-Ukraine energy strategy in the Eastern Mediterranean, while Rome has given the required diplomatic backing to help reduce geopolitical risk and move alternative supply routes toward a successful close.

ENI and Europe’s Post-Ukraine Energy Realignment

The Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered a dramatic collapse of Russian gas exports to Europe, forcing a desperate search for alternative suppliers. Russia’s pipeline deliveries to the EU plummeted from about 146 bcm in 2021 to barely 62 bcm in 2022, losing its status as Europe’s top gas supplier. By 2023, Russian gas had shrunk to a minor fraction of Europe’s supply (under 15% in total, with only ~7% via pipelines). Italy, which was once heavily reliant on Gazprom, also decreased Russian gas purchases by over 50%, replacing them with flows from Algeria, Azerbaijan and LNG imports. In this situation, ENI’s ties with North African, such as Algeria, Libya, and Egypt, and Subsaharan producing countries, such as Nigeria, Mozambique, and Angola, were essential in securing new pipeline flows and LNG imports. LNG emerged as Europe's lifeline, jumping from 32% of the EU’s gas supply in 2021 to 37% in 2023. In 2025, ENI made a 20 year LNG sales and purchase agreement with US LNG producers, Venture Global. By 2023, Russian gas made up less than 5% of Italy’s intake.

Amid the situation, Italy launched an ambitious strategy to reinvent itself as Europe’s southern energy getaway. This strategy, referred to as “Mattei Plan”, after ENI’s founder Enrico Mattei, envisions Italy as the main entry point for energy (especially natural gas) from North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean into Europe. ENI and the Italian government moved in 2022-23 to lock in new partnerships and infrastructure that would leverage the country;s position at the center of the Mediterranean. First with the state visits to Algeria in July 2022 and in early 2023, and then to Libya in 2023. These moves increased Algerian gas exports to Italy, making Algeria Italy’s top supplier of gas, and boosted Libyan gas output via the GreenStream pipeline to Italy.

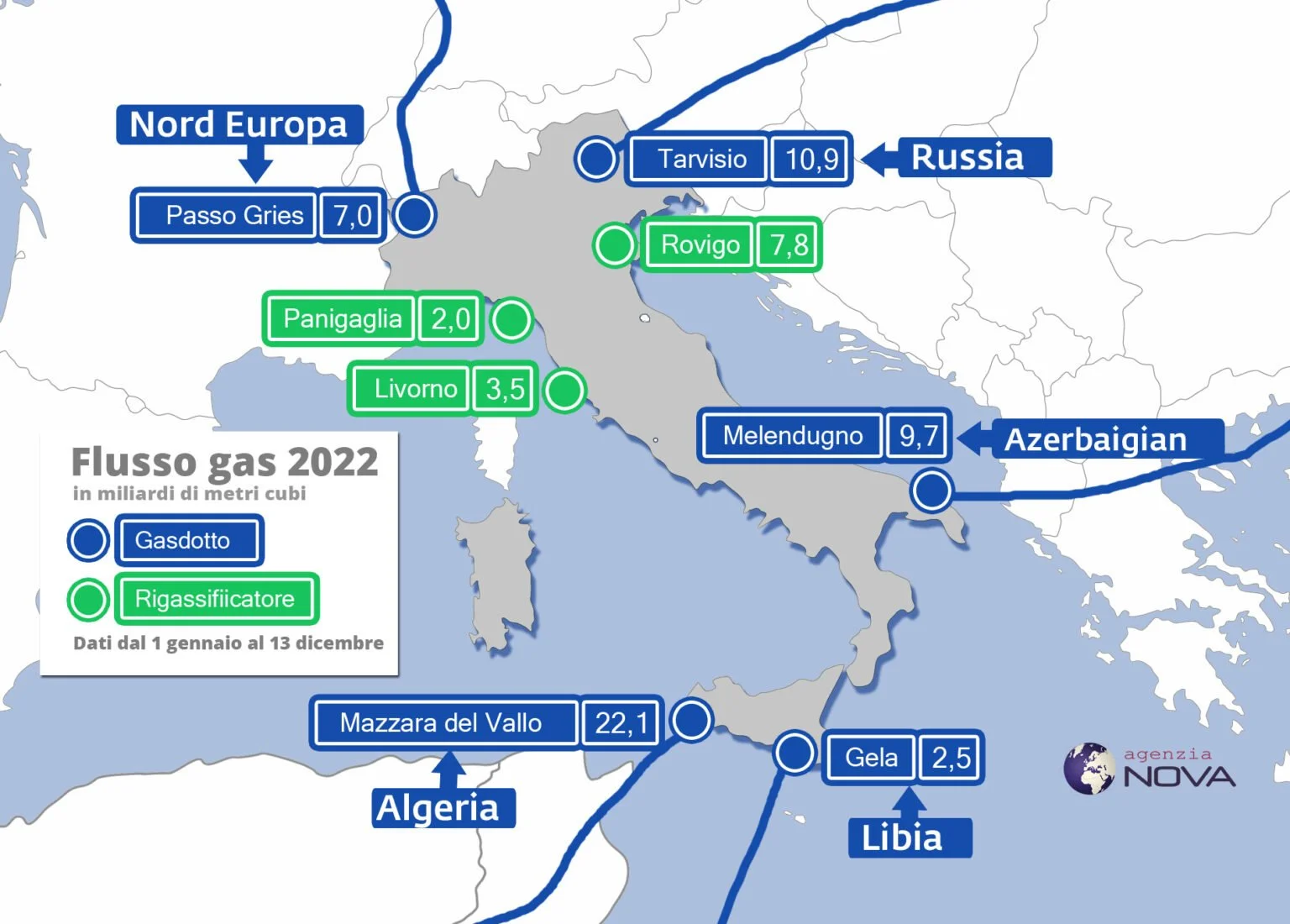

Major pipelines linking Italy to producing countries, Agenzia Nova 2022

Italy is uniquely positioned to be an energy conduit, with multiple import pipelines from the Mediterranean region. Three major pipelines land in Italy;’s south: the TransMed from Algeria (via Tunisia), GreenStream from Libya, and the TAP from Azerbaijan via the Adriatic. These combined with Italy’s growing LNG import capacity, form a platform for Italy to redistribute gas further into Europe. In fact, Italy has been rapidly expanding LNG terminals, adding floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) at Piombino and Ravenna, which will nearly double its LNG import capacity from 14.5 MTPA in 2023 to ~25 MTPA by 2030. The extra capacity enables more shipments from diverse suppliers like the U.S., Qatar, and Africa. Italy also boasts Europe’s second-largest gas storage volume ( ~197 TWh), allowing it to stockpile gas and manage seasonal flows. All these assets support Rome’s vision of re-exporting gas northward: Italy is exploring pipeline upgrades (e.g. an “Adriatica” pipeline expansion by 2027) to send gas to Austria, Bavaria and beyond). Even Egypt and Israel have expressed interest in sending their gas to Europe via Italy.

Crucially, Italy’s gateway approach goes well beyond fossil gas, with the Mattei Plan positioning Italian energy co-operation in Africa as a “virtuous model of collaboration” encompassing gas development but also tying this to the development of renewables, hydrogen, and electricity connections, as reflected in the 2022 Algerian agreement concerning green hydrogen, ammonia, and renewables. In this respect, Italy asserts the strategic value of the southern gateway not as a reorientation towards hydrocarbons but rather as a transition from the current gas infrastructure system to a low-carbon future approach, even if this contradicts the EU’s long-term vision of a decarbonized future and a likely contraction in gas demand in the region.

ENI thus appears as the main conduit through which Italian energy strategy was transformed into Mediterranean geopolitical power, especially in the aftermath of the Ukraine war. Through quick augmentations in pipeline deliveries from Algeria via the TransMed pipeline, development of fixed Mediterranean gas deliveries from Libya via the GreenStream pipeline, and Italian leadership in Mediterranean LNG partnerships with Egypt and Qatar, ENI helped Italian gas imports reduce dependence on gas imports from Russia while consolidating Italian status as an entry point into the EU energy market in Southern Europe. This took place in close coordination with Italian statecraft foreign policy strategies via ENI-sourced gas import deals signed in tandem with bilateral summits. More importantly, however, the Mediterranean diplomacy embodied in ENI’s activities encompasses much more than gas resources. Whereas a generation ago gas agreements essentially focused on the sale of gas, the new agreements entail a multiplication of areas of cooperation that combine gas resources, renewable sources, hydrogen, and infrastructure development, thus implying a will to use today’s gas transport corridors as launched platforms for tomorrow’s decarbonized transports. In this way, ENI enables Italy to position itself not only as a transit country, but as a role-player in brokering a connection between the energy security of Europe and the development needs of the African continent and the Middle East.

ENI’s Hybrid Identity: Corporate Autonomy and Statecraft

“State influence” refers to ownership, board nomination channels, and the application of Italy’s golden power framework, not to day-to-day operational control.

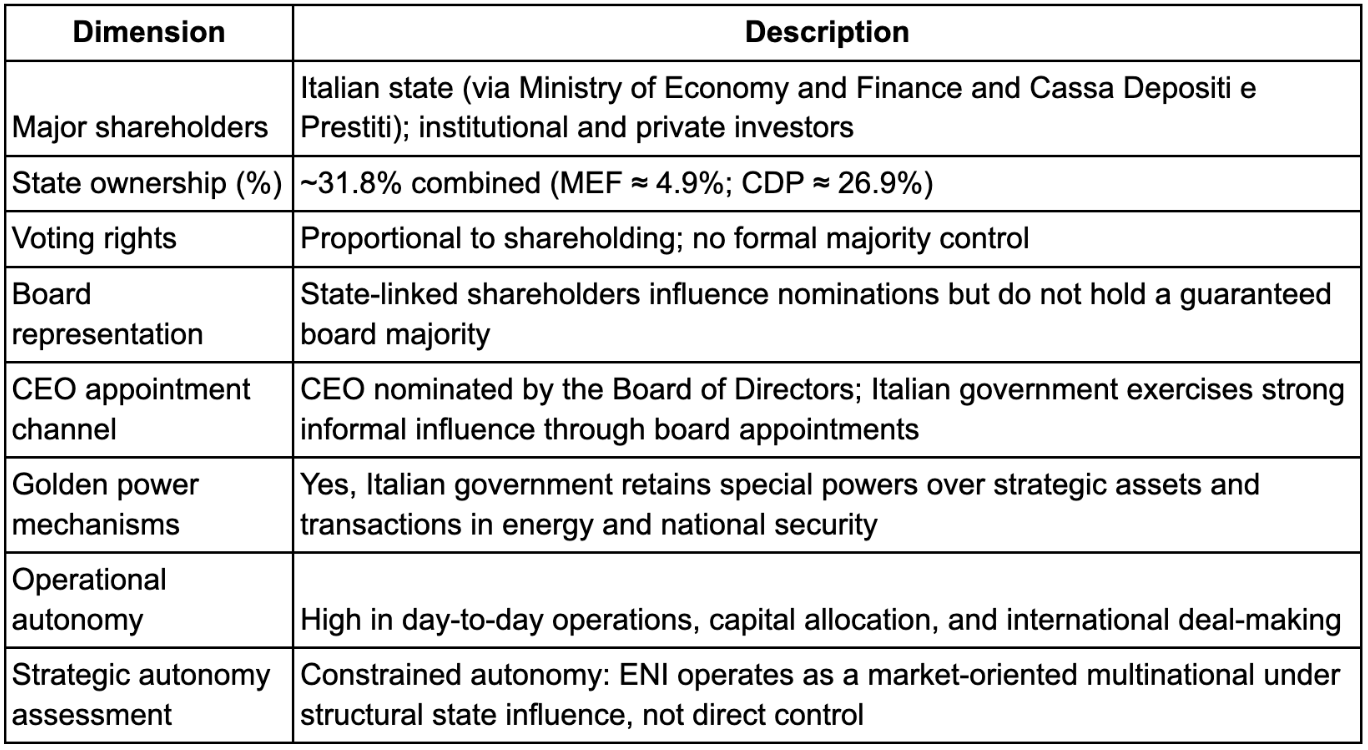

ENI’s governance reflects a hybrid identity, since it is publicly traded and operates with commercial autonomy, yet about one-third of its shares are owned by the Italian government. As of 2025, the Ministry of Economy and Finance (via Cassa depositi e Prestiti) holds rough;ly 31.8% of ENI’s equity, giving the state de facto control. This means that while Eni enjoys operational independence and a mandate to maximize shareholder value, the Italian state can exert influence over major decisions (for example, through board appointments and strategic direction). ENI’s ownership structure and governance mechanisms, summarized in the following table, which illustrate how the company operates under significant state influence without being subject to direct state control.

The government’s stake ensures that national strategic interests, such as energy security and foreign policy goals, remain coherent with Eni’s corporate objectives. Eni’s partial state ownership stems from its origins. Enrico Mattei, Eni’s founder, established the company in 1953 as a state-owned entity dedicated to securing Italy’s energy supply in the post-war era by providing 75% of profits to host nations and by establishing close ties with producing countries also by supporting their anti-colonial movements. As of today, the company still prides itself on a degree of corporate autonomy and national mission that is uncommon among oil majors. For example, Eni’s top executives often move in step with Italian diplomatic initiatives, and the Italian government typically nominates Eni’s CEO, ensuring alignment with national policy. At the same time, Eni must answer to private shareholders and international markets, which imposes financial discipline and transparency typical of a public corporation. This governance balancing act allows Eni to operate like a commercial major while still acting (when convenient) as an instrument of Italian statecraft.

I. Business-Driven Geopolitics

ENI’s global strategy is characterized by a business-driven geopolitics, which consists in securing oil and gas resources across the world, and it is therefore not guided by ideology but by the company’s commercial interests. Compared to supermajors like Chevron or TotalEnergies, Eni operates with a smaller capital base, yet it consistently punches above its weight through diversification, risk appetite, and technological mastery. A core feature of ENI’s strategy has been its diversification of supply. In fact, ENI maintains an expansive portfolio of upstream assets from North and West Africa (Algeria, Libya, Angola, Egypt, Nigeria) to the Middle East and beyond, ensuring that no single region dominates its resource base. Also, ENI has shown willingness to enter politically risky environments, often thanks to its early entry. An example of this is ENI’s presence in Libya through the years of the civil war and instability post-2011, when a lot of competitors left the country. By keeping operations running (especially gas production) and working with whichever authorities controlled Tripoli, Eni entrenched its position as Libya’s leading foreign energy operator. Similarly, ENI was an early mover in places like Mozambique and Egypt, in which it discovered two big gas fields, such as Zohr in Egypt in 2015 and Mamba gas fields in Mozambique in 2011-12. For ENI, technological innovation has been an important equalizer. In fact, according to ENI, from 2008 to 2016 it discovered around 13 billion barrels of new resources, adding reserves at an average cost of only $1.20 per barrel, about 20% of the industry average. This remarkable record can be attributed to cutting-edge seismic imaging of the HPC supercomputer. Under this approach, Eni fast-tracks the evaluation and development of new finds while simultaneously seeking partners to farm into the project. By moving quickly from discovery to production, Eni shortens the time to cash flow, and by selling down stakes in the finds, Eni capitalizes on its exploration success to raise capital for reinvestment. Indeed, selling portions of big assets has become a hallmark of Eni’s financial strategy. For example, in the Zohr field, ENI swiftly sold 40% combined stake to BP and Rosneft for over $2 billion in 2016, just a year after discovery. The influx of cash funded development costs and bolstered Eni’s balance sheet during an oil price slump due to oil oversupply caused by the 2016 oil oversupply caused by the Shale revolution, high OPEC output and slowing demand from China, illustrating how Eni leverages partnership and project flips to compensate for its smaller capital relative to oil majors. ENI’s business-driven approach to geopolitics also means it negotiates with host countries to secure favorable terms, often trading technical expertise or infrastructure investment for access, making it a contributor to broader economic developments. This echoes Mattei’s old playbook of pairing oil contracts with local benefits.

II. Balancing Political Guidance and Commercial Logic

A central tension in ENI’s hybrid identity is the balance (sometimes a trade-off) between political guidance from Rome and pure commercial logic. As a partially state-controlled enterprise, Eni historically has aligned with Italy’s foreign policy goals, but as a profit-seeking company, it must also pursue ventures that make business sense, even if they are politically sensitive. This dynamic creates both synergies and tensions in ENI’s decision-making. On the one hand, the Italian government’s strategic outlook often guides Eni’s priorities abroad, creating synergy between national interest and corporate interest. Nowhere is this more evident than in Libya, a country of paramount importance to both Italy and ENI. ENI supplies much of Italy’s imported natural gas from Libya (via the GreenStream pipeline), making Libyan stability a national concern. During Libya’s civil conflict in the 2010s, Italy’s policy heavily favored the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli, a stance influenced in no small part by the fact that almost all of ENI’s Libyan oil and gas assets are located in the GNA-controlled western region. In effect, Italy needed the GNA to survive and prevail in order to secure ENI’s infrastructure. An analysis by the Real Instituto Elcano notes that Italy has a “vital national interest in the preservation of the GNA” precisely to ensure the security of Eni’s energy operations (Di Camillo, 2009). This alignment led to close cooperation: Italy provided diplomatic and even limited military support to Tripoli, while Eni maintained gas flows that kept both Italian and Libyan electricity grids stable.

In this case, political and commercial logics worked together, as ENI’s success allowed Italy to achieve energy security and Italy’s diplomacy protected ENI’s investments.

Often, ENI acts as an icebreaker for diplomatic ties while expanding its market share across different regions. For example, Eni’s major gas discoveries in Mozambique in the 2010s were followed by growing Italian diplomatic and economic attention to that country. Likewise, in Egypt, Eni’s pivotal role in the gas sector (with Zohr and other fields) has reinforced Italy’s political partnership with Cairo.

On the other hand, there are times when tensions arose, especially when ENI’s commercially rational partnerships conflicted with Italy’s broader political alignments. ENI used to enjoy long-standing joint ventures and gas import contracts with Russia’s Gazprom and Rosneft, but since the 2014 Crimea annexation and the later escalation of US and EU sanctions on Russia, ENI was forced to scale back or freeze cooperation despite their commercial value. An example of this was the selling of its 50% stake in the Blue Stream pipeline (in the Black Sea to Turkey) and the halt of joint drilling operations with Rosneft in the Black Sea. Similar constraints applied to ENI’s exposure in Iran and Venezuela, where repayment mechanisms and upstream stakes became increasingly difficult to sustain. This shows how geopolitical pressure can disrupt market logic and limit ENI’s operational autonomy.

III. Competition in the Mediterranean Area

The Mediterranean basin is one of ENI’s geographical priority and it has become increasingly crowded with competitors, from traditional oil majors like TotalEnergies and BP to newer entrants including US firms and Gulf state companies. Eni remains a central player in the Mediterranean energy landscape but it is witnessing the loss of its long-standing dominance, especially in Egypt and Libya. In Libya, which used to be ENI’s stronghold, the reopening of exploration rounds after years of conflict has attracted major rivals such as TotalEnergies, Chevron, and ExxonMobil, signaling a shift toward a more competitive market. In the Eastern Mediterranean, Eni’s Zohr discovery in Egypt initially gave it a first-mover advantage, but it also triggered an influx of competitors including BP, Shell, Chevron, ExxonMobil, and QatarEnergy across Egypt, Cyprus, Israel, and Lebanon. As a result, Eni now operates in a multipolar environment where competition and cooperation coexist: it partners with firms like TotalEnergies in Cyprus and Algeria for political and risk-sharing reasons, while directly competing with BP, Chevron, and others for new areas of explorations and influence.

IV. Corporate Diplomacy and Accountability

Eni’s long-standing practice of corporate diplomacy has positioned the company as a powerful non-state actor, particularly in fragile and conflict-affected states. This approach is most visible in Libya, where Eni maintained relations with rival factions during the civil war to safeguard its gas infrastructure, even stepping into quasi-governmental roles. In 2020, for example, Eni signed an agreement with the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord to help restore electricity supplies during a severe power crisis, leveraging energy provision as both a stabilizing tool and a means of protecting its operations. Such situations blur the line between corporate activity and diplomacy and might raise some ethical questions on accountability when a company exerts political leverage without democratic oversight. Similar challenges arise in day-to-day operations, as Eni has had to navigate militia control, security vacuums, and shifting alliances in Libya, or contend with militancy, environmental damage, and social unrest in Nigeria’s Niger Delta. These governance and ethical tensions are most starkly illustrated by the OPL 245 corruption case in Nigeria, where Eni and Shell paid over $1 billion for offshore oil rights that ultimately benefited intermediaries and political elites rather than the Nigerian state. Although Eni’s leadership was acquitted by an Italian court in 2021, the case damaged the company’s reputation and became emblematic of the difficulties of enforcing accountability in global energy operations. In response, Eni has emphasized strengthened compliance frameworks and expanded its corporate social responsibility agenda, promoting development-focused initiatives such as infrastructure investment and the Italian-backed “Mattei Plan for Africa.” As a partially state-owned firm, Eni faces heightened expectations to reconcile commercial success with ethical responsibility, making its hybrid role of corporate actor and instrument of state influence, both a strategic asset and a persistent source of controversy.

Conclusion

Since February 2022, ENI has acted as both an enabling instrument of Italian and European energy strategy and an independent geopolitical vector actively shaping the energy outcomes in the Mediterranean. Italy's diversification pivot in North Africa relied heavily on ENI’s infrastructures and relationships: the increased of Algerian supplies through TransMed, the 2023 $8 billion offshore deal with Libya's NOC designed to revive the country's production and make full use of GreenStream's spare capacity, and ENI's deep integration into Egypt's gas system via Zohr and Damietta-all served to reinforce Italy's claim to the status of Europe's southern energy gateway. ENI's stakes in Cyprus, its entry into Israel and Lebanon, combined with the more hub-style solutions routing regional gas through Egypt's LNG plants, illustrate how corporate project design can reconfigure regional connectivity and export pathways in ways supportive of EU diversification.

At the same time, however, the paper reveals that ENI's behavior cannot be reduced to state direction; its deal-making reflects a distinct business-driven geopolitics-risk tolerance in fragile environments, in Libya, for example; technological acceleration, as in fast-tracking Zohr; and partnership strategies aimed at monetizing assets and managing capital constraints. This hybrid identity produces both synergy and friction: Rome's diplomacy often de-risks ENI's operations and amplifies its bargaining power, while ENI's commercial footprint pushes Italian policy toward pragmatic engagement with contested actors and difficult governance contexts. ENI, therefore, ultimately serves as a hybrid channel through and by which Italy translates energy security goals into Mediterranean influence-but at the same time enjoys autonomous agenda-setting discretion on infrastructure choices, partner selection, and regional hub architecture, with all that implies for thereby becoming both a tool of statecraft and a geopolitical actor in its own right.