A Deep Dive Into Moldova's Latest Elections

By Aiden Perry

History

Russia's interest in Bessarabia, the eastern european region of which Moldova comprises the majority, dates back over 2 centuries. The Russian Empire first annexed the territory from the Ottomans in 1812, in the aftermath of the 6 year Russo-Turkish war. From then it enacted a policy of russification, seeking to cultivate a Russian identity in local elites. The success of this policy was mixed, as Romanian identity and nationalism remained strong enough that the region was reintegrated into Romania in the aftermath of the disintegration of the Russian Empire following 1917, despite more than a century of Russian rule.

Moldovan unification with Romania proved to be short lived however, as the new Soviet Union seized Bessarabia back from Romania in 1940, unifying parts of the south and north with the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, territory that is still part of Ukraine today, and establishing the new Moldavian SSR with the remaining territory in the center of the region. Romanian rule briefly returned from 1941-1944 with the Romanian invasion of the Soviet Union during WWII, but following the defeat of the Axis powers, it was agreed that the Soviet-Romanian border would return to the pre-1941 boundary, leaving Moldova in Soviet hands.

The Soviets, like the imperial Russians before them, continued to attempt to russify the territory. In addition to declaring Russian the official language, they also declared that the Moldavian dialect of Romanian was its own distinct language, a language that was to be written using the cyrillic alphabet. Party Secretaries of the Moldavian SSR were typically Russian in origin, including future General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Leonid Brezhnev. The authorities in Moscow also facilitated the movement of large numbers of ethnic Russians to the territory, many of these ethnic Russians found themselves living in Transnistria, a thin strip of land to the east of the Dniester river, and to the west of the Ukrainian border. A phenomenon that later fueled war in Moldova following independence. Soviet efforts at russification were more successful than those of the Russian Empire, but ultimately failed at making a Russian Moldova. In 1989, the Moldavian SSR’s Supreme Soviet established Romanian, written in Latin script, as the sole official language of the republic. Less than a year later, the republic, which was now referring to itself as the Republic of Moldova, declared its sovereignty, and asserted its laws were supreme over the laws of the USSR. Thirteen months following its declaration of sovereignty, Moldova declared its independence following the failure of the August Coup in Moscow in 1991.

The nascent republic, having just freed itself from Moscow’s grasp, immediately found itself coming back under Russian influence. The Russians in Transnistria refused to recognize rule from Chisinau, claiming that it was invalid on the basis of Moldova’s own declaration of independence and its denunciation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact that established that the lands east and west of the Dniester were to be unified. War erupted, and Russian soldiers deployed to the territory, securing the de facto independence of Transnistria, and creating a territorial dispute that would prevent Moldovan accession into NATO and the European Union.

Russia and Moldova enjoyed relatively warm relations following the conclusion of the Transnistria war in 1992, despite Russian troops’ presence. Moldova joined the newly formed Commonwealth of Independent States, and successive Moldovan governments sought not just to balance relations between Moscow and the West, but often, particularly under the administrations of presidents Voronin and Dodon, outright favored Moscow. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Moldovan leaders routinely emphasized neutrality, avoided discussions of NATO membership, and relied heavily on Russia for energy supplies and access to migrant labor markets. Even during periods of political tension, such as the Communist Party’s electoral losses in 2009 or disputes over gas pricing, both sides maintained a pragmatic relationship shaped by economic interdependence and shared Soviet-era institutional linkages. This relative stability began to erode in the late 2010s, and by around 2020 relations deteriorated sharply as Moldova accelerated its pursuit of European integration, adopted a more assertive anti-corruption agenda, and elected leaders, most notably Maia Sandu, who openly challenged the influence networks Moscow had cultivated for decades.

Electoral

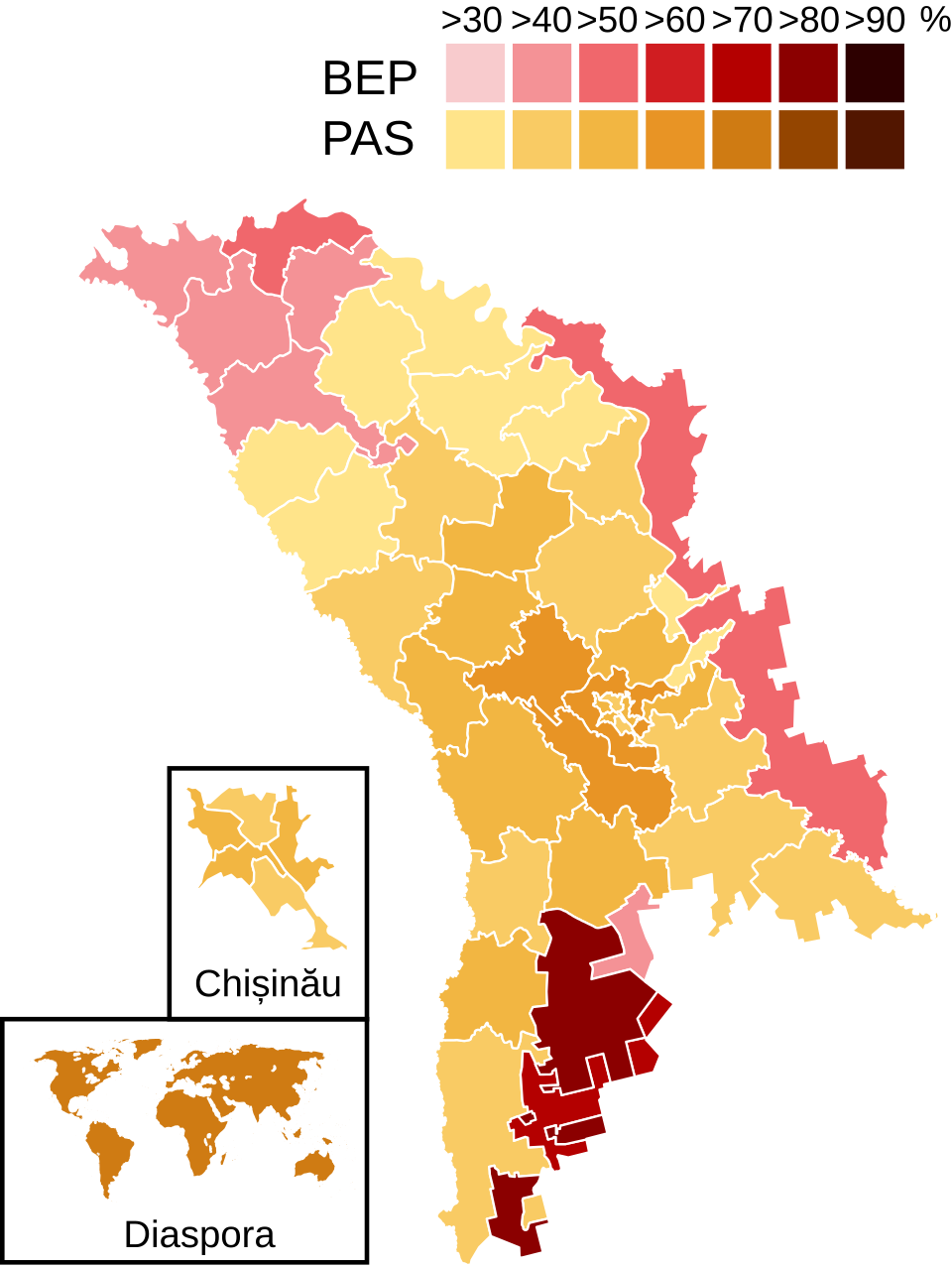

On September 28, 2025, Moldovans went to the polls in an election that was to determine not just the next several years of Moldovan policy, but the country’s future for decades to come. Moldovans were presented with the options of continuing European integration through reelecting Maia Sandu’s Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), or orienting itself in a firmly pro-Russian direction by electing the Patriotic Electoral Bloc (BEP), an alliance of left-wing, Russophilic parties. The recently annulled election of pro-Russian candidate Georgescu in Romania in 2024 loomed in the minds of people in both Chisinau and Moscow, with Moscow fearing that a pro-Russian victory might be annulled, and those in Chisinau fearing a return to Russian control. As results came in, it quickly became clear that Sandu’s party had triumphed, and that the country would for the time being continue on the path of European integration.

Russia’s failure to secure a victory in the Moldovan elections was not for a lack of trying. Russia has, for years, dedicated heavy resources to ensuring Moldova stays within its sphere of influence. Before the BEP, Russia’s primary vehicle of influence in Moldova was the Shor party, so named after its founder, Ilan Shor. Through the use of the sanctioned state owned Russian bank Promsyvazbank Russia would funnel money into Shor’s coffers for the purposes of vote buying, paying protestors, and paying campaign rally attendees. In addition to Ilan Shor himself, Russia made strong use of one political figure, the governor of the Gaugauzia province, Yevgenia Gutsul. Gutsul’s political platform openly called for deepening Moldova’s ties with Russia, Gutsul traveled to Moscow on several occasions, where she met with and was photographed with Vladimir Putin at least once. In her publicized meeting with Putin, she referred to “lawlessness” in Chisinau, and claimed that Chisinau was attempting to economically blockade the Gaugauzia region. Using this rationale, she advocated for the introduction of the Russian Mir payment system, a substitute for SWIFT.

In response to her subversive activity, Gutsul was sanctioned by both the United States and the European Union, before ultimately being arrested and sentenced to 7 years in prison for her legally undisclosed, but open use, of Russian funding. Gutsul however was not an anomaly, a previous governor of Gaugauzia, Irina Vlah, who also stood for election this past September, similarly acted as a Russian agent, making multiple undisclosed visits to Moscow during her tenure. Her Heart of Moldova party was part of the BEP, before being excluded two days before the election following revelations that it too, took Russian funding, the Bloc did this hoping to avoid a fate similar to its predecessor Shor, which was deemed to be illegal by the Moldovan Constitutional Court in 2023 due to its Russian connections.

Even though Shor’s party was banned in 2023, that did not stop his political activity, he founded the Victory Bloc in 2024 in a conference not in Chisinau, but in Moscow. The decision to launch the bloc on Russian soil signaled both his dependence on Russian political protection and the extent to which the movement functioned as an external operation directed from abroad rather than a domestically rooted party. From Russia, Shor coordinates the bloc’s messaging, financing, and organizational structure, relying heavily on guidance from Russian political strategists who had previously shaped the activities of the Shor Party. The Victory Bloc was the Kremlin’s preferred vehicle for influence in Moldova following the banning of the Shor Party, but the bloc’s overtly Russian nature proved to be its undoing. Even Moldovans who are in favor of close ties with Russia found themselves disillusioned with how the bloc seemed to be Russian before Moldova, with Ilan Shor now residing in Russia after having obtained Russian citizenship, and stating that he believes the only path forward for Moldova is to enter into a Union State with Russia, an arrangement that would see Moldova transformed into a Russian client state similar to Belarus.

Information and Energy

In addition to its more traditional methods of developing pro-Russian political networks, Russia also tries to undermine Moldovan sovereignty using two other distinct tools, information, and energy. In the year preceding the 2025 election, Russia drastically ramped up its efforts to weaken Moldova, starting by cutting off gas to its Transnistrian proxies in December 2024. This decision created an immediate crisis on the left bank of the Dniester, where Transnistria’s economy and public services rely almost entirely on subsidized Russian gas. Heating systems shut down, the main power plant suspended operations, and factories halted production. Entire districts lost electricity and hot water, schools were forced to close, and the separatist administration entered an emergency footing in which all exports of electricity were suspended, including to the rest of Moldova. Although the halt in supply was framed as a technical consequence of expiring transit arrangements and unpaid Moldovan debts, Moscow used the crisis to signal to voters that Moldova’s westward trajectory carried real material risks.

The shock created by the cutoff quickly spilled across the Dniester. Although Moldova had spent the previous two years reducing its dependence on Russian gas, it still relied heavily on electricity generated in Transnistria’s Cuciurgan power plant. Once Transnistria suspended all exports, Moldova was forced to turn to far more expensive imports from Romania and European markets. Consumers and businesses experienced higher energy prices, and the government was pushed to allocate emergency funds to stabilize the grid. Even though the administration in Chisinau managed to prevent widespread blackouts, by cutting off energy supplies, Moscow sought to convince Moldovan voters that the country remained vulnerable to Russia, and thus ought to remain in Russia’s good graces.

In addition to trying to scare the domestic Moldovan electorate through power shortages, Russia also tried to convince the Moldovan diaspora that it should refrain from voting for the PAS, or indeed refrain from voting at all. In April 2025, Russia’s two principle information warfare programs, dubbed Overload and Matryosha (nesting doll) drastically increased references to Moldova. The programs seek to impersonate reputable foreign news outlets, producing content in Romanian, Russian, and English, and spread falsehoods relating to PAS’s activity. The Russian disinformation operation has accused PAS and Sandu of being “dishonest” and of corruption similar to that of its own proxies in Shor and the BEP. These efforts aimed to create a sense in Moldovan citizens living abroad that PAS represented more of the same governance that the country had been under since its independence, more of the same governance that has plagued many eastern european countries, a nominally democratic system ruled by corruption and Soviet style overbureaucracy.

Conclusion

Just as in Romania, Russian efforts at influencing the Moldovan parliamentary elections ultimately failed. BEP only secured around 24.2% of the vote, a net loss of 3% from its predecessor’s 2021 electoral performance. PAS won 52.8% of the vote, securing a majority in parliament strong enough that it could govern on its own without having to enter into a coalition. The people of Moldova made a clear choice, choosing to continue on a pro-western path of European integration over a return to Russian domination.