The Fragmentation of Transatlantic Order and the EU’s Internal Vulnerabilities: Corruption, Cohesion and the Future of European Rule-making

By Andrea Radoman

The initial conception of the EU was largely based on trade agreements intended to better help neighboring countries by limiting—or eliminating—tax. In centuries prior the idea of some system to join together Europe was floated quite a few times, whether it be as early as the 15th century and a proposition to unite the Christian kingdoms of Europe together in order to end military conflict between Christian nations (Treaty on the Establishment of Peace Throughout Christendom 1464) or the theoretical concepts in the 17th and 18th centuries proposed by William Penn, Charles-Irénée Castel de Saint-Pierre, and Immanuel Kant, which would serve as forums for conflict resolution between states. The previously proposed idea that is the most akin to the modern day EU is the Congress of Vienna in 1815, which gathered the great powers of the time to reestablish order on the continent toward the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Despite many notions of a unified Europe, it was not until after World War I that more earnest measures of creating it were undertaken. With the United States’ growing strength across the ocean and financial ruin plaguing many countries after the war, a union that was more financial in nature was considered, and can best be summarized by John Maynard Keynes, who stated that, “a Free Trade Union should be established ... to impose no protectionist tariffs against the produce of other members of the Union.” The Council of Europe in 1949 was the first established institution in post war Europe, but it was only intergovernmental in nature and did not lead to more unity. All this to say that Europe has spent the vast majority of its long history as a collection of separate, independent states, a system that worked for a very long time. The union it finds itself in today is a product of the 20th century, even if the idea is one long predating it. Based on general sentiment rippling throughout the transatlantic, it looks like European unity might soon be a result of the recent past, as opposed to being on the future’s horizon.

Internal Discontent

The primary benefits of being a member of the EU are: goods flow freely, minimal taxing on goods, easy travel between countries due to border regulations, emboldened sentiments of unity, human rights guidelines, and support to each other’s economies during times of financial distress. Coincidentally, the very things that make the EU beneficial are also what can make membership a liability.

Human rights regulations—such as having a certain quota of immigrants or refugees that must be accepted—can lead to dissatisfaction in a state by the people who face the consequences of such policies. Having support from other countries also seems appealing on paper, until several poorer countries with weak economies require assistance, and require richer countries to raise taxes on their people or divert money intended to improve their own lands in order to help the ones in crisis, as was the case during the Eurozone crisis starting in 2009, right after the global financial crisis of 2007. Europe as a whole amassed great debt in the process of attempting to bail out the worst affected countries—Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain—causing widespread protest amongst member countries who had to raise taxes and sacrifice their trade by constraining their imports and production of exports to save money. In order to divert the crisis, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) intervened, and the European Financial Stability Facility (ESFS) was created, but the reform on fiscal and monetary policy caused much internal turmoil, with dissolution of the Union being brought up in the process.

Many countries were opposed to the IMF intervening. The European financial assistance was taxing on member states because it involved raising taxes and diverting money from their own countries to the Union to be distributed, namely to Greece as it received the first financial aid package. Compared to the Greece crisis, which totalled €289 billion in aid packages—which still wasn’t enough to restore market stability. While that in and of itself was controversial enough, the IMF’s interference upset many countries—one of the most notable being France—because many felt it discredited the euro and EU countries. Since the IMF had previously only gotten involved in matters relating to developing countries like during the Latin America crisis, and crippled European self-determination, because a bigger institution unaffiliated with Europe got involved with an issue that was supposed to be their own. Through the perspective of majority parties in certain countries, it was an undermining of authority and an insult to their capability. In the past decade, the EU’s defensiveness over individual identity has only grown in significance as an issue. This can largely be traced back to the refugee crisis caused by the Syrian Civil War, when 4.5 million (nearly a fifth of the country’s pre-war population) people from Syria alone fled their country. Once again, governments allocated money to issues not concerning their people, but rather those outside the country, in this case, outside of the continent. To put an exact figure, Austria alone spent €21 billion on institutions, housing, and other costs for accommodating migrants. The bill for other countries who had an even more drastic rate of immigration—like France and Germany—have spent much more.

Rising nationalistic sentiment has also contributed to issues within individual states. Adding to the disapproval from people regarding diversion of funds is the appearance of being put in second place. As shown by the Eurobarometer evaluation, the majority of Europeans identify more with their country and ethnicity than with being European. The title of “European” resonates strongly within every one of these countries, but does not overrule national identity, meaning that if individual governments—or the EU itself—made laws that would stifle said ethnic identity, it’s not farfetched to say there would be calls to leave the Union. As was the case with Brexit, the main reason behind the referendum of leaving was a desire to have more sovereignty and control over immigration. Working class citizens in particular voted to leave—since they felt they had been forgotten in favor of big picture politics—with the wealthier, urban citizens wanting to stay, mostly due to the ease of trade provided. Specifically, households with an income of less than £20,000 were more likely to vote against remaining in the EU—as well as those with only a high school education or lower—while the wealthiest households voted more in favor. The majority of Britain felt as though they were not receiving enough care and attention as citizens of their own nation, because the UK government was prioritizing EU laws and what would be beneficial to the Union over its own people. There is still debate over whether or not Brexit was a good decision, but it was a decision made by the people, not politicians, which ultimately has the final say. Big picture politics makes sense from the position of a statesman on the world stage, but a government’s priority should always be itself and the people directly under its care. If they lose sight of their own subjects, then they’ve lost sight of their one and only purpose.

Internal Corruption

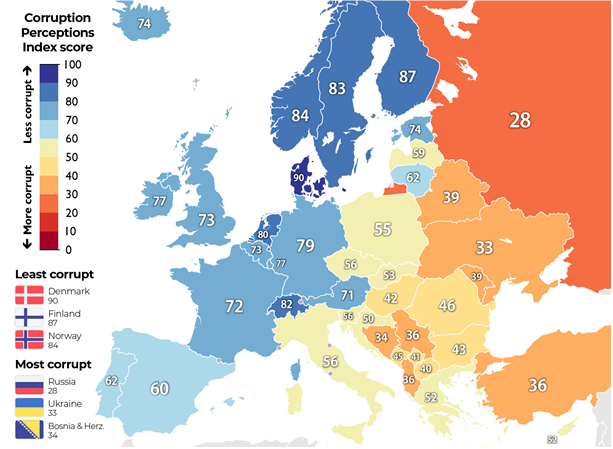

Thus far, only the problems countries have with the EU have been listed, but not individual problems in the states, particularly regarding the government. Corruption within the member countries also affects their policies toward the Union, as is evident from the Corruption Perception Index (CPI). The CPI uses data on bribery, diversion of public funds, officials using their public office for private gain without facing consequences, nepotistic appointments in the civil service, state capture by narrow vested interests, and access to information on public affairs/government activities, to determine corruption, or more specifically lack of transparency to government activities. According to the CPI, Scandinavian countries scored lowest in corruption, with Hungary being the most corrupt. Corruption negatively affects passage of laws, as lawmakers can often focus their policies around what their donors want and not the benefit of the people, prioritizing the security of their position instead. This includes taking bribes and forging pacts with other countries—whether they be in or out of the EU—in a way that is more beneficial to themselves than sticking to the regulations outlined by the EU. Even if measures to rectify or punish these countries were taken, it would likely be viewed as the European Parliament overstepping its authority. With the EU primarily serving economic and trade functions, meddling too much with the government structure of their members would be frowned upon, particularly because some—like the (French) Left Front and AFD (German) parties—are already of the mindset that immigration quotas and certain other standards are too intrusive.

That said, corrupt governments are contributors to the EU’s weakness and inability to enforce certain laws, or fully abide by their vow of transparency. Governments with high corruption are by nature the opposite of transparent and weaken the overall union, which is powerless to impose any meaningful measures against it. The reason seems to be that the EU itself is corrupt and undemocratic, as shown by both Qatar Gate and the new fraud probe in December 2025. Qatar Gate is perhaps one of the most notable examples of the EU failing to police itself and maintain the standards outlined for the organization and its members. In this case, many senior staff within the Parliament accepted bribes from Qatar meant to garner supportive votes from the EU regarding its human rights and labor laws ahead of the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Little is known about the exact details, since there were no convictions made, even after two detainees confessed. For something that exposed fundamental, structural flaws, it was swept under the rug quietly and efficiently.

The most recent instance of bribery, on the contrary, might have more of a lasting impact and chance at visibility, featuring senior EU figures connected to the European External Action Services (EEAS). Belgian authorities, working with the European Public Prosecutor’s Office, launched an investigation into suspected fraud and conflicts of interest tied to the creation of the EU Diplomatic Academy. The case drew particular attention because it involved well-known and influential figures, including former EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini, who now serves as rector of the College of Europe, one of the allegedly benefitting institutions. While no convictions have been made here either, the investigation raised questions about transparency, procurement practices, and accountability within the EU’s own bureaucracy. Much like Qatargate, the scandal highlights a recurring pattern: the EU is quick to criticize corruption and governance failures at the national level, yet struggles to convincingly demonstrate that its own institutions are held to the same standard. The fact that such allegations emerged from within the EU’s diplomatic and administrative core only reinforces perceptions that corruption is not an external problem threatening the Union, but an internal one that it remains poorly equipped to address.

America’s Role and Disengagement

With the United States’ partial disengagement from the global stage under the Trump administration, questions surrounding the European Union’s ability to function with reduced U.S. support have been brought to the forefront. This shift has exposed existing fractures within the EU, particularly as the U.S. adopts a more selective approach to its alliances, favoring countries that align closely with American interests—such as Italy, Austria, Poland, and Hungary—over those that do not. Americans themselves have quite varying opinions on what their role should be. Some are still for a transatlantic alliance, content with sending funding, weaponry, and other assistance to Europe, but others question why the U.S. keeps meddling in affairs outside of its borders instead of fixing pressing internal issues. For some, the individual alliance approach—having obligations to individual countries instead of the entire EU—would be better, since it is a more flexible commitment, the terms of which are more easily negotiable.

This external pressure intersects directly with the Union’s internal weaknesses. Dissatisfaction stemming from economic redistribution, migration policies, and governance failures has eroded solidarity among member states, leaving the EU ill-equipped to respond collectively when external support is suspended. The result is an organization that struggles to act cohesively, not from a lack of formal authority, but because it does not have the political unity and institutional trust necessary to exercise it. Corruption and elite opportunism further exacerbate this problem, undermining the EU’s credibility as a regulatory power and reinforcing perceptions that compliance is optional rather than binding.

Taken together, these dynamics significantly weaken the EU’s ability to function as a cohesive governing body. Falling public approval ratings, reduced legislative productivity, increased internal spending disputes, and stalled policymaking all point to a long-term decline in institutional effectiveness that has been visible since the early twenty-first century. Although there was a brief resurgence of unity following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, that momentum gradually faded as national interests once again took precedence, reflected quite clearly by the continued purchasing of Russian oil. Even in a conflict posing a direct threat to some member states, the EU’s collective response lagged behind that of the U.S. in both military aid and coordination, while several countries continued to purchase Russian energy despite formal sanctions. When observing the contribution of military, financial, and humanitarian aid, the U.S. contributes as much if not more (depending on the source of the exact figure) than the EU, which is a collection of 27 countries with some of the highest GDPs in the world, to Ukraine. If the Union cannot sustain a unified response in the face of such an immediate and shared threat, it underscores the broader conclusion that personal and national interests have increasingly taken priority over broader interests, revealing the EU’s limited capacity to act as a truly cohesive regulatory authority.

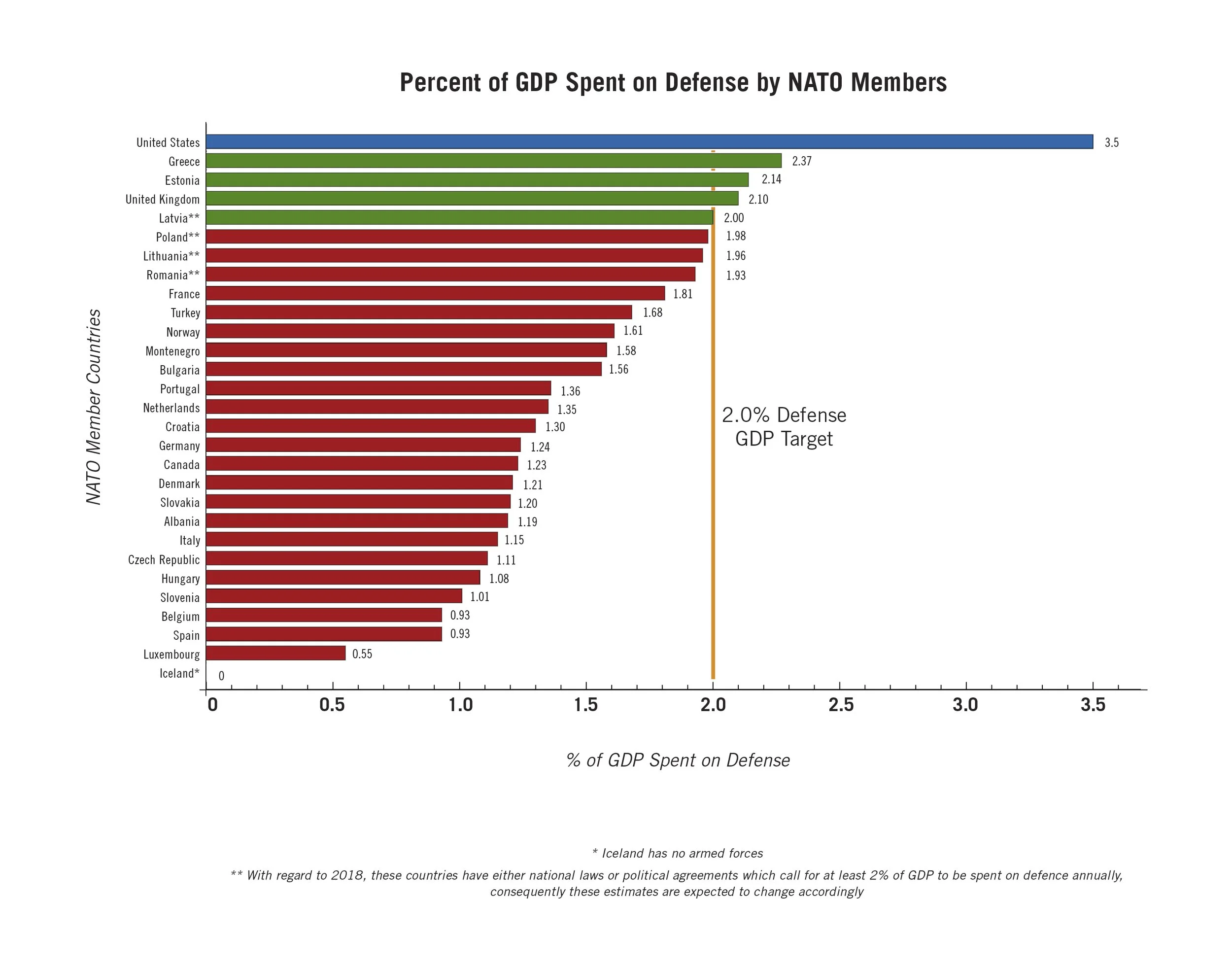

American withdrawal from international organizations also forced individual countries, such as Britain and France, to come to terms with their lack of defense, since the entire continent has been so heavily reliant on American force and funds for decades.

This granted the U.S. more bargaining power in individual alliances, with select countries as opposed to the whole union whose policies it no longer aligns with. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)—the military force that goes hand in hand with the EU and American partnership—has also been dealt a heavy blow by the withdrawal of troops and funding from Europe. With fears regarding Russia's next actions, this is something they can not afford nor withstand.

What is the Way Forward?

The EU has served as a symbol of unity for Europe since the end of World War II, whether it be in an official or unofficial capacity, but it seems its expiration date is fast approaching. The economic appeal it holds might soon be outweighed by corruption within the top level, a lack of military power, and regulations that are both too lenient and too intrusive for some of its most important member states. As is the case with the entire continent, the EU must adapt to the times and prepare for an overhaul of its outdated principles if it hopes for a future in a rapidly changing world, one that could feature it taking a backseat in favor of hegemons such as the U.S., India, and China. If the EU was to instead go back to serving only its primary purpose—as a trade union—and cut back on immigration regulations that infringe on the authority of state governments, its lifespan has the potential to be much longer. Keeping the euro for ease of trade, but adjusting the perspective that Europe is a unified country equivalent to that of the U.S. Even the U.S.—a sovereign country with a constitution and much more cohesion than the EU—has substantial domestic problems which people are calling for solutions to because of how different every state and its constituents is. Cutting out the bureaucracy of unelected officials in the European Parliament and focusing on improving internal trade relations/policies combined with individual alliances could aid with stabilization going forward, since the current system appears to be heading toward an imminent collapse.