Gender and Political Corruption in Ukraine (1991-2025)

By Valentina Scassiano

Introduction

According to Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index, Ukraine ranks 122nd, behind countries such as Egypt and Peru for levels of corruption perceived by the population. This indicator captures a broader structural reality highlighted in the literature: for decades, business and politics in Ukraine have been deeply intertwined, the rule of law has remained weak, and informal payments have permeated nearly every interaction with the state, from accessing medical care to running a business or financing political campaigns. Political and bureaucratic offices have often been allocated through patronage networks, in which powerful elites extract rents and distribute income to their associates, depriving the state of resources at every level.

This system has resulted in a fragile public service culture, while ordinary Ukrainians have learned to be self-reliant and frequently perceive the state as predatory rather than as a provider of public goods. At the same time, the boundary between legal and illegal practices remains blurry for much of the public, and petty bribery is widely accepted as an expected means of “getting things done.”

If some have argued that a “corruption culture” derived from the Soviet period still shapes the everyday life perception of bribing and corruption in Ukraine, this phenomenon can be observed also in the highest spheres of the government. The 2013-2014 Euromaidan revolution disrupted but did not dismantle this system: the political leadership that emerged from the protests often maintained one foot in the old oligarchic order and one in the reformist demands voiced on the streets. Despite the creation of new anti-corruption institutions and some legal improvements, the fight against grand corruption, for the purpose of this paper defined as the abuse of high-level public office for private enrichment - has made limited progress.

Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022 has further complicated this landscape, bringing renewed scrutiny to a series of high-level scandals.

At a moment when Ukraine faces a 35% contraction in GDP, World Bank estimates, and a budget deficit of 38 billion USD in 2023, credibility has become one of the country’s most vital assets. Ukraine’s survival depends heavily on sustained international assistance, and any failure to ensure effective monitoring of the massive inflow of aid could jeopardize both the war effort and future reconstruction. Understanding the persistence of high-level corruption, as well as the political and institutional obstacles to reform, is therefore not only academically relevant but essential for assessing the country’s prospects in the years ahead.

In this context, an interesting angle from which to examine corruption in Ukraine is the role of gender. A growing body of international research suggests that men and women may differ in their propensity to engage in corrupt practices, in their perceptions of corruption, and in their everyday experiences with it. Despite ongoing efforts toward greater gender equality, women remain significantly underrepresented in Ukrainian political institutions.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate whether women in high-level government positions in Ukraine are less likely to be involved in corruption, and, if so, to identify the underlying reasons. The study will consider the time frame going from the first post-Soviet governments to present days (August 1991 - October 2025) and focus only on grand corruption involving high-stake decision makers. The main hypotheses are the following:

(1) women may have fewer opportunities to engage in corruption due to their more limited access to political posts;

(2) women may be concentrated in ministerial portfolios that are less susceptible to corrupt practices;

(3) women may be, in general, less inclined to participate in corruption due to differences in attitudes or behavioural tendencies, or to socialization, or to differences in access to networks of corruption, or in knowledge of how to engage in corrupt practices, or to other factors.

Brief history of corruption practices in independent Ukraine

This section provides a brief overview of major corruption scandals in Ukraine. It then examines the role of women in high government positions and their near-absence from corruption scandals, before drawing preliminary conclusions.

Since its independence on August 24, 1991, political corruption has been a persistent feature of Ukrainian governance. In the first period after Soviet rule, electoral fraud, the misuse of public office for private gain, and the manipulation of state assets have undermined public trust. Major scandals have repeatedly involved political elites. In 2000, the Cassette Scandal implicated President Leonid Kuchma in alleged threats against journalist Heorhiy Gongadze, who was later murdered while investigating corruption, with opposition leader Oleksandr Moroz playing a key role in exposing the case. In 2004, widespread electoral fraud during the presidential elections involving Viktor Yanukovych and other officials triggered the Orange Revolution. Former Prime Minister Pavlo Lazarenko was convicted in the United States in 2006 for laundering approximately $200 million and extorting Ukrainian businesses, marking one of the country’s most notorious cases of grand corruption. During the 2010-2014 Yanukovych administration, massive embezzlement and corruption networks emerged, with the Mezhyhirya estate symbolizing the extravagant theft of state resources. More recently, Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov (2019-2023) was involved in multiple procurement scandals, including the “eggs for 17” controversy, overpriced winter jackets, and inflated contracts for military food supplies, leading to his resignation following investigations by the National Anti-Corruption Bureau. Other high-profile cases include Deputy Minister Vasyl Lozynsky’s arrest for allegedly accepting a $400,000 bribe, and the resignations of Deputy Defense Minister Viacheslav Shapovalov and former Deputy Head of the President’s Office Kyrylo Tymoshenko for misuse of public or donor resources. Anti-corruption reforms in Ukraine have been sporadic and partially effective: agencies such as the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption were established after Euromaidan, but enforcement remains weak, political interference persists, and the 2020 Constitutional Court ruling rolled back key legislation. The war since 2022 has further strained oversight and diverted resources, limiting the state’s capacity to monitor corruption.

In recent weeks, Ukraine has been shaken by a major corruption scandal involving high-profile figures close to President Volodymyr Zelensky. According to The Guardian (2025), the president dismissed Justice Minister Herman Halushchenko and Energy Minister Svitlana Hrynchuk following allegations connected to a large-scale bribery scheme in the national energy sector, with the main suspect identified as Timur Mindich, a former business partner of Zelensky and co-founder of Kvartal 95. The investigation, conducted by the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) and named “Operation Midas”, documented that Energoatom’s contractors were forced to pay kickbacks of 10–15% of contract values to avoid payment delays or losing supplier status. The case raised concerns about the independence of anti-corruption bodies, as Zelensky had approved a controversial law in July 2025 that reduced the powers of NABU and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO), which was later amended under public pressure to restore their autonomy. The scandal, which also includes audio recordings using code names for suspects and involves high-ranking female officials, highlights the persistence of structured corruption networks and the difficulties faced by the Ukrainian government in balancing anti-corruption efforts with internal political pressures, representing a significant challenge to the narrative of transparency and integrity promoted by the Zelensky administration.

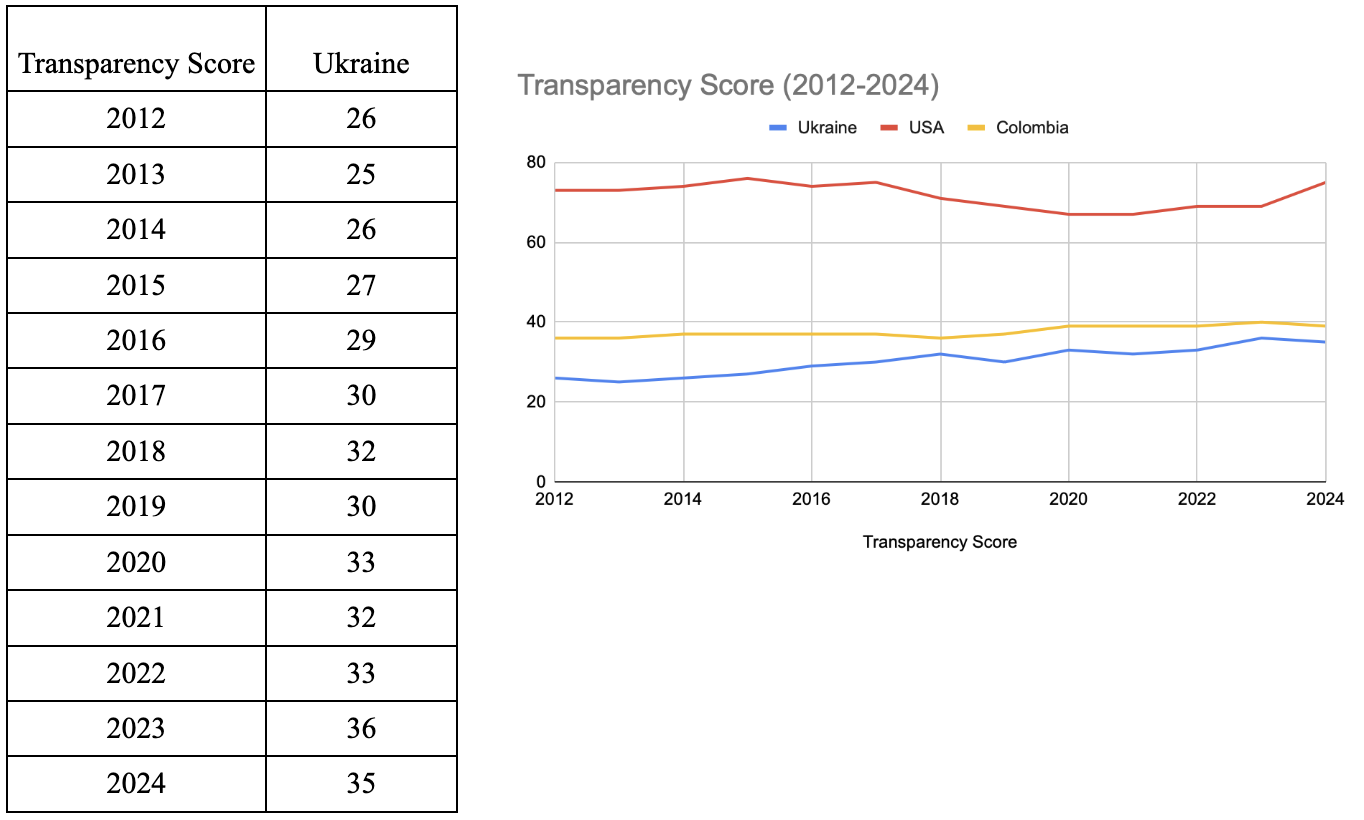

Transparency Score (2012-2024)

Transparency International. (2025). Ukraine. Transparency International.

As for gender, from 1991 to 2025 it is possible to identify only 43 out of 433 ministerial positions covered by women in total. As an example, there is still no gender balance in the current government, the second led by Yulia Svyrydenko and confirmed in July 2017: only 3 out of 15 ministers are women, or 20%. This is below the European average of 32%. Although the current 20% of women ministers remains far from European standards, for Ukraine it represents a significant step forward. For a long time, women’s participation in government was almost symbolic: in most Cabinets before 2014 it did not exceed 10%, and in many cases it was 0%. Only a few governments achieved more substantial progress; the record was set by Oleksii Honcharuk’s Cabinet, where women accounted for 40% of ministry heads.

Among those, only 3 ministers were investigated for corruption and embezzlement of funds, before the current case involving Svitlana Hrynchuk: Yulia Tymoshenko, Raisa Bohatyriova and Natalia Korolevska, about whom information is scarce and fragmented.

Yulia Tymoshenko, a former energy-sector entrepreneur and head of United Energy Systems of Ukraine (UESU), entered high-level politics in 1999 as Deputy Prime Minister for Energy. She later served twice as prime minister - in 2005 for 9 months and later from 2007 to 2010 - and became one of the most visible figures of the post-Orange Revolution period. The first set of allegations emerged in 2001, when Tymoshenko was dismissed from the government, arrested, and briefly detained on charges related to corruption, tax evasion, and fraudulent financial operations connected to UESU during the 1990s. These accusations concerned alleged illicit gas-trading schemes and undeclared earnings involving UESU’s dealings with Russian energy suppliers. The charges were eventually dropped, and Tymoshenko consistently claimed they were politically motivated.

A more consequential phase began after her second premiership (2007 - 2010). Under President Viktor Yanukovych, prosecutors revived scrutiny of her governmental decisions, particularly her negotiation of the 2009 gas contract with Russia. Investigators argued that Tymoshenko had exceeded her authority and committed abuse of office by authorizing an agreement that imposed inflated prices and was allegedly detrimental to Ukraine’s economic interests. In 2011 she was formally tried and convicted for abuse of power under Article 365 of the Ukrainian Criminal Code and sentenced to seven years in prison. The proceedings attracted extensive criticism from the EU, the US, and international legal observers, who argued that the trial failed to meet international standards, selectively applied the law, and appeared designed to marginalize a key political opponent.

In late 2011, additional charges were issued against her, including allegations of large-scale tax evasion, embezzlement, and the misuse of UESU funds in the mid-1990s. These cases likewise stemmed from her activities in the energy sector and were widely viewed as part of a broader campaign of legal pressure by the Yanukovych administration.

In 2013, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) decided in Tymoshenko v. Ukraine (Application No. 49872/11), concluding that Yulia Tymoshenko's pre-trial incarceration in 2011 breached various sections of the European Convention on Human Rights. The Court ruled that the imprisonment was arbitrary and politically motivated, compromising the norms of fair trial and judicial independence. The ECtHR specifically stated that the Ukrainian courts engaged in procedural flaws, selectively interpreted the law, and failed to offer adequate basis for her ongoing incarceration. This decision fueled worldwide allegations that Tymoshenko's trial under President Viktor Yanukovych was not only legitimate, but was primarily aimed to eliminate a political opponent.

Tymoshenko was released in February 2014 after the fall of Yanukovych, when the Ukrainian parliament annulled the statute under which she had been convicted. Her release effectively nullified the legal force of the 2011 judgment, which by then had been broadly characterized - both domestically and internationally - as an instance of politically motivated justice rather than substantiated corruption.

Bohatryova’s case is more straightforward. Raisa Bohatyriova, former Minister of Health under President Viktor Yanukovych, became the subject of multiple corruption investigations following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution. On 20 October 2014 she was formally designated as a suspect in a case of large-scale embezzlement involving approximately 6 million dollars in state budget funds. The following day she was placed on the national wanted list, and a court ordered the seizure of several properties owned by her and her husband, including apartments in Kyiv and Yalta and three houses in the village of Pidhirtsi (Obukhiv Raion). In early March 2014, the European Union had already frozen her assets on suspicion of unlawful appropriation of public funds. On 12 January 2015, Interpol issued a red notice for Bohatyriova on charges of misappropriation, embezzlement, and related malfeasance. Ukrainian authorities later reported that she had reimbursed the allegedly misappropriated sums, which led to the unfreezing of her assets in the EU. During the subsequent years, Bohatyriova’s whereabouts remained unknown, and Ukrainian prosecutors sought permission to conduct a special pretrial investigation in absentia, arguing that she had deliberately evaded investigative and judicial procedures. In 2015 the Prosecutor General’s Office submitted multiple mutual legal assistance requests to foreign jurisdictions in an effort to obtain documentary evidence of her illicit activities; these remained pending for several years.

Bohatyriova reappeared in Ukraine on 27 August 2019, arriving at Kyiv’s Zhuliany Airport, where she was immediately detained by the National Police. She was released from pretrial detention two days later after member of parliament Vadym Novynskyi posted bail on her behalf.

No further details on the development of the case have been found in journalistic or academic sources. The latest news dates back to August 2019.

To conclude, while the allegations against Yulia Tymoshenko are not fully substantiated and may have emerged in a highly polarized political environment, they nonetheless represent the most prominent corruption-related scandals involving women in high political office in Ukraine with the conviction of Raisa Bohatryova.

Having established a general overview of the topic, the following sections will undertake a more detailed analysis of our hypothesis.

Women limited access to power

The empirical evidence appears to support the first hypothesis: women have fewer opportunities to engage in corruption because they have more limited access to political office. From 1991, the year of Ukraine’s independence, to 2019, women held on average 7.8% of ministerial positions in each government. In some cabinets, female representation reached 0% (particularly between 1993 and 1997). This proportion increases substantially after 2019: in the last four governments, Oleksii Honcharuk (August 29, 2019 - March 4, 2020), Denys Shmyhal (March 4, 2020 - July 16, 2025), and Yuliia Svyrydenko (from July 17, 2025 onwards) - women make up approximately 25% of ministers, marking a significant improvement for Ukraine but still remaining below European average.

Therefore, women’s lower involvement in corruption scandals appears largely attributable to their persistent underrepresentation in positions of political power, which structurally limits their exposure to opportunities for corruption. It is noteworthy, however, that the recent increase in women’s ministerial participation over the past five years has not been accompanied by any new corruption scandals involving female ministers - despite a general rise in corruption cases linked to the outbreak of the war and the management of international assistance.

At the same time, the two governments with the highest proportion of female ministers prior to 2019 - Viktor Yushchenko’s (December 22, 1999-April 28, 2001), with 13%, and Mykola Azarov’s (December 24, 2012-February 21, 2014), with 11% - are precisely those in which the only two corruption scandals involving female ministers occurred. This alone is obviously not enough to establish any type of causal relationship or strong correlation between the two variables. To highlight this pattern more clearly, a more systematic quantitative analysis would be required, though this remains difficult due to the scarcity of comprehensive and reliable datasets.

Nonetheless, it can be stated with reasonable confidence that while women’s underrepresentation helps explain their lower participation and visibility in corruption practices, it cannot fully account for the phenomenon, suggesting that additional structural or contextual factors may also be shaping these outcomes.

Gendered allocation of Ministerial Portfolios and exposure to corruption practices

A second hypothesis that may help explain the lower involvement of women in corruption scandals in Ukraine is that women tend to be appointed to ministerial portfolios that are structurally less susceptible to corrupt practices. The distribution of ministerial posts held by women provides some support for this possibility, although it is not conclusive.

Table 1

The most frequently held portfolio among women is the Ministry of Social Policy, which is primarily responsible for welfare provision, social protection, family support, and the development of human capital. The ministry’s activities focus on service delivery rather than large-scale public procurement or management of state-owned enterprises, and, as such, it may present fewer opportunities for corrupt enrichment.

The second most common positions occupied by women are the Ministry of Justice and the office of Prime Minister, each held three times.

Other ministries frequently held by women include Healthcare, Education and Science, Energy, Veterans Affairs, and Culture, each represented twice. Deputy minister positions held by women, which are not included in Table 1, are disregarding a thematic approach, the largest category.

Yulia Tymoshenko served first in 1999 as Deputy Minister for Energy and then twice as Prime Minister, when allegations of corruption were made against her. Similarly, Raisa Bohatyriova, who served as Vice Prime Minister while holding the Healthcare ministerial post, faced corruption allegations linked to procurement, illustrating how combined roles can increase access to state contracts and funds.

Similarly, corruption cases among men predominantly involve positions with extensive control over financial flows and procurement. For example, Viacheslav Shapovalov, Deputy Defense Minister, resigned following revelations that the ministry had paid inflated prices for food supplies for the armed forces. Similarly, Oleksii Reznikov, Minister of Defense from 2021 to 2023, was implicated in procurement scandals, including the widely publicized “eggs for 17 hryvnias” controversy. Historical cases reinforce this pattern: Pavlo Lazarenko, a former Prime Minister, was convicted in the United States for laundering approximately 200 million dollars and extorting businesses, while the presidencies of Viktor Yanukovych and the premiership of Mykola Azarov (2010 - 2014) were marked by massive embezzlement schemes and systematic misuse of state assets.

Taken together, these cases suggest that corruption in Ukraine tends to concentrate regardless of gender in ministries with high budgetary discretion and decisional power, such as Defense, Finance, and the Prime Minister’s office.

However, this apparent concentration must be interpreted with caution. The available data, often derived from media reports and investigative journalism, disproportionately focuses on high-level officials and ministries managing substantial resources, particularly during wartime. Consequently, the visibility of corruption may be skewed toward male-dominated offices, not only because these positions are inherently more corruption-prone, but also because they attract greater scrutiny.

Moreover, some ministries held by women, such as Energy or Veterans Affairs - which involve substantial public funds - have not reported major corruption scandals. Overall, the evidence provides partial support for the hypothesis that women are overrepresented in portfolios less exposed to corruption. Nevertheless, this remains far from conclusive, and the strongest explanatory effect appears so far to be that proposed by the first hypothesis.

Gendered perception and attitudes toward corruption

In this section, we discuss hypothesis 3, which posits that women may, in general, be less inclined to participate in corruption due to differences in attitudes or behavioral tendencies, socialization, access to networks of corruption, knowledge of corrupt practices, or other factors.

Over the past decades, a notable pattern has emerged, showing a strong correlation between higher levels of women’s political participation and lower levels of corruption.

Swamy et al. provide evidence that, in hypothetical scenarios, women are less likely to condone corruption, women managers are less involved in bribery, and countries with greater female representation in government or the labor market tend to exhibit lower levels of corruption. While the study does not identify the underlying mechanisms, it documents statistically robust relationships indicating a clear gender differential in tolerance for corruption.

Zhytkova et al. examine the case of Ukraine through a small-scale pilot survey.

The study relies on 50 survey responses from individuals born and residing in Ukraine, of which approximately 76% are female. The limited scope and gender distribution of the sample were influenced by the war conditions following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, as many Ukrainian men were involved in the conflict. The survey included questions exploring political activism, personal experiences with corruption, and perceptions of corruption in the country. The findings suggest that women are more exposed to day-to-day corruption than men, which aligns with broader research indicating that men occupy higher positions of authority and dominate political, economic, and other key sectors. Furthermore, women have been shown to be more risk-averse and less likely to engage in corrupt practices than men.

Differences in attitudes toward corruption between men and women have been explored in several studies. Dollar et al. highlighted that women are more likely to sacrifice personal gains for the common good, making them less prone to engage in corrupt behavior. These arguments are largely supported by prior behavioral research, which shows that women score higher on integrity tests and demonstrate stronger adherence to ethical norms.

Finally, although Ukrainian men are more likely to engage in activism or politics, Ukrainian women are more likely to experience corruption. Zhytkova et al. also indicate that corruption poses greater challenges for women than for men, potentially due to male domination in key societal sectors and the prevalence of informal corrupt networks controlled by men. It is therefore possible that women, being more vulnerable to the effects of corruption due to their lower representation in positions of power and greater exposure to corrupt practices, tend to perceive corruption more negatively.

Additionally, women may experience greater social and professional pressure to conform to anti-corruption norms. Since women are often underrepresented in positions of power and must overcome higher barriers to reach such offices, they may feel compelled to exemplify irreproachable behavior. Women are frequently judged more harshly for mistakes, particularly in contexts with limited oversight, which may further discourage engagement in corrupt practices. Consequently, when the risks of being caught are high, women may be less likely to participate in corruption.

Limitations and further research

This study faces several limitations. First, the available data is largely derived from online news articles and journalistic sources, reflecting the difficulty of accessing structured academic datasets on Ukraine in this specific context. As a result, the analysis is necessarily fragmented and may be influenced by reporting biases, with high-profile cases receiving disproportionate attention. There is a clear need for more systematically collected and objective data, particularly from a post-war perspective, when academic research will be crucial in providing policymakers with insights on how reconstruction processes may affect patterns of political corruption and to support the rebuilding of the Ukrainian government and society.

Second, the analysis presented here is primarily descriptive and correlational. Quantitative research, including regression analyses, is necessary to move from correlation to causation and to rigorously test hypotheses regarding the relationship between gender, ministerial portfolio allocation, and corruption. This relates to the lack of data and organised datasets.

Finally, further research should investigate whether the methods of corruption differ by gender. It is possible that women engage in corrupt practices that are less visible or that their corruption could be less frequently reported in the public media.

It could also be relevant to examine the effects of network formation among politicians who remain in office for longer periods. For example, if men tend to hold ministerial posts for longer durations - also when they hold different ministries across different governments and cabinet reshuffles - this may facilitate the creation and consolidation of corruption networks.

Moreover, future research should focus on the relationship and influences between the gender-specified impact of corruption that makes women more vulnerable to negative effects of corruption practices and women representation in high-stake political roles.

Exploring these possibilities would provide a more nuanced understanding of gendered patterns of corruption and inform more effective policy interventions.

Conclusion

The analysis presented in this paper partially contributes to demonstrate that the near-absence of women in major corruption scandals in Ukraine cannot be attributed to a single factor but emerges from a combination of structural, institutional, and behavioural-context dependent dynamics. The first and most empirically supported explanation is the persistent underrepresentation of women in high-level political offices. With women historically occupying less than 10% of ministerial posts until 2019, their limited exposure to the arenas where grand corruption typically occurs reduces their opportunities to participate in large-scale illicit activities.

The second hypothesis, concerning women’s concentration in ministerial portfolios that are less vulnerable to corruption, receives partial support. Women in Ukraine have most frequently held positions related to social policy, education, and culture - sectors that manage comparatively smaller budgets and face lower procurement risks than ministries such as Defense.

The third hypothesis addresses gendered differences in attitudes and perceptions of corruption. Scholarly literature consistently suggests that women tend to be more risk-averse and more sensitive to social sanctions than men.

Survey-based evidence, although limited, indicates that women perceive corruption more negatively and experience its consequences more directly, reinforcing their incentive to distance themselves from corrupt practices.

As Ukraine moves toward EU integration and post-war reconstruction, increasing women’s participation in high-level politics may contribute not only to democratic inclusiveness but potentially to greater institutional integrity. Further research is, thus, needed.