Echoes of Empire: The Resurgence of Nationalism and Fascist Symbolism in Post-Communist Romania

By Luca Guerzoni

Echoes of Empire: The Resurgence of Nationalism and Fascist Symbolism in Post-Communist Romania

In May 2025, Romania’s presidential election displayed a pivotal choice between competing visions of the country’s future. In high-turnout runoff, Nicusor Dan, the centrist and pro-European mayor of Bucharest, narrowly defeated George Simion, the ultraconservative and nationalist opposition leader of the Alliance for the Union of Romanians party (AUR), by 53,6% to 46%.

Despite Dan’s victory being praised by the European Union and his voters, it is important to note the unprecedented breakthrough of nationalist discourse in post-communist Romania. This appeared first in the first round of the November 2024 presidential election, where independent candidate, Calin Georgescu, won with 23% of the vote, ahead of many candidates. Georgescu managed to tap into a vein of discontent among the Romanians towards the European Union via TikTok. A lot of his campaign was characterized by support for conservative values such as traditional family, sovereignty, and ‘end to corruption and foreign diktat’, while his stance in foreign policy were openly anti-NATO and tended to be echoing the Kremlin propaganda. He also praised Romania’s WWII controversial figures such as WWII-time leader, Ion Antonescu, and Iron Guard leader, Cornerliu Zelea Codreanu.

Right before the second round, Romania’s Constitutional Court annulled the first-round results, accusing Russia of having orchestrated Georgescu’s rise, with the support of Romanian warlord, Horatiu Porta. This led to widespread protest across Bucharest, as many viewed this decision to be ‘undemocratic’ as it effectively halted a democratic decision, and it was heavily criticized by anti-establishment parties across Europe and by tech billionaire Elon Musk. Calin Georgescu was ultimately banned from re-running the election planned for May 2025, a decision that contributed to the Economist’s evaluation that Romania is the least democratic country in the European Union in 2025.

After Georgescu’s exclusion, George Simion became the leading nationalist and conservative leader of the AUR. In his campaign, he publicly denounced the court's decision over Georgescu – labelling it an ‘EU coup’ – and was an outspoken critic of the European Union. Despite being less favorable to Russia than Georgescu, he seemed to be a hardliner domestically and called for unification with Moldova. In the first round of the May 2025 election, Simion secured a 41% of the votes, nearly double that of the runner-up Nicusor Dan. Despite the final proclamation of Nicusor Dan as the seventh president of Romania, it is notable that even in defeat, Simion’s AUR had managed to become the second-largest political force in Romania.

First Round of May 2025 Election Results

Analysts have observed that multiple politicians across Romania’s right wing political spectrum, such AUR’s George Simion and Calin Georgescu, have expressed long-standing public nostalgia for the country’s interwar fascist figures and conservative Orthodox values, and have used that to channel popular anger at mainstream elites and ‘Western’ influence, mostly identified as coming from the European Union. This electoral drama raises questions about the historical undercurrents still shaping Romanian politics. The key to understanding the persistence of skepticism and fascist ideologies in Romania’s contemporary politics is analyzing the country’s complex imperial legacies.

Imperial Influences on Romanian Nationalism

Romania’s modern national identity was forged in resistance to centuries of imperial domination. In fact, what is today Romania was located at the crossroad of three different empires: Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman.

The medieval principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia were long under Ottoman suzerainty, which reinforced an Eastern Orthodox orientation in resistance to the Muslim rule of the Sultans in Istanbul but also preserved local autonomy and Latin-derived linguistic culture.

National chronicles often celebrate medieval princes who fought to preserve their independence from the Turkish Invaders, thereby also defending Christianity in Europe. In contrast, in Transylvania and Bukovina, decades of Habsburg domination fostered a distinctive Mitteleruoepan spirit. In these regions, Romanian populations endured Austro-Hungarian rule, facing political marginalization as ethnic Romanians were forced to work as serfs for ethnic Hungarian landlords and nobles. Again, resistance to the Austro-Hungarian rulers built up a sense of ethnic consciousness and reinforced a still-growing anti-Hungarian sentiment. Similarly, the Russian influence was felt in the northeastern region of Bessarabia, where the Russian Empire’s annexation in 1812 following the Treaty of Bucharest spread Russian influence in the Balkans, countering the Ottoman Empire’s hold in Southeastern Europe. Russia proceeded by integrating the local elites known as boyars and used them to advance Russification policies to destroy the population’s predominantly Moldovan/Romanian identity. Because of its proximity to the Russian Empire and the persistent threat of Russification and cultural erasure, the city of Iași emerged as the capital of Romanian nationalism, where where local intellectuals, clergy, and political leaders fiercely resisted imperial influence by cultivating Romanian language, literature, Orthodox traditions, and national consciousness as acts of defiance and identity preservation.

The culmination of these imperial legacies came after World War I, as the collapse of the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian empires drove the previously subjugated Romanian-inhabited regions to unite in 1918. The new state of Greater Romania, which lasted from 1918 to 1940, realized nationalist aspirations but also introduced the new state to the persistent clash between ethno-cultural homogeneity and nationalist desires, particularly in its western border with Hungary and in its northern border with Russia (or the Soviet Empire). The legacy of foreign rule and other struggles to reclaim sovereignty have fundamentally shaped Romanian nationalism, embedding notions such as defender of faith, unity against occupiers, and cultural distinctiveness into modern day political campaigns and national narrative.

The Iron Guard and the Rise of Fascism

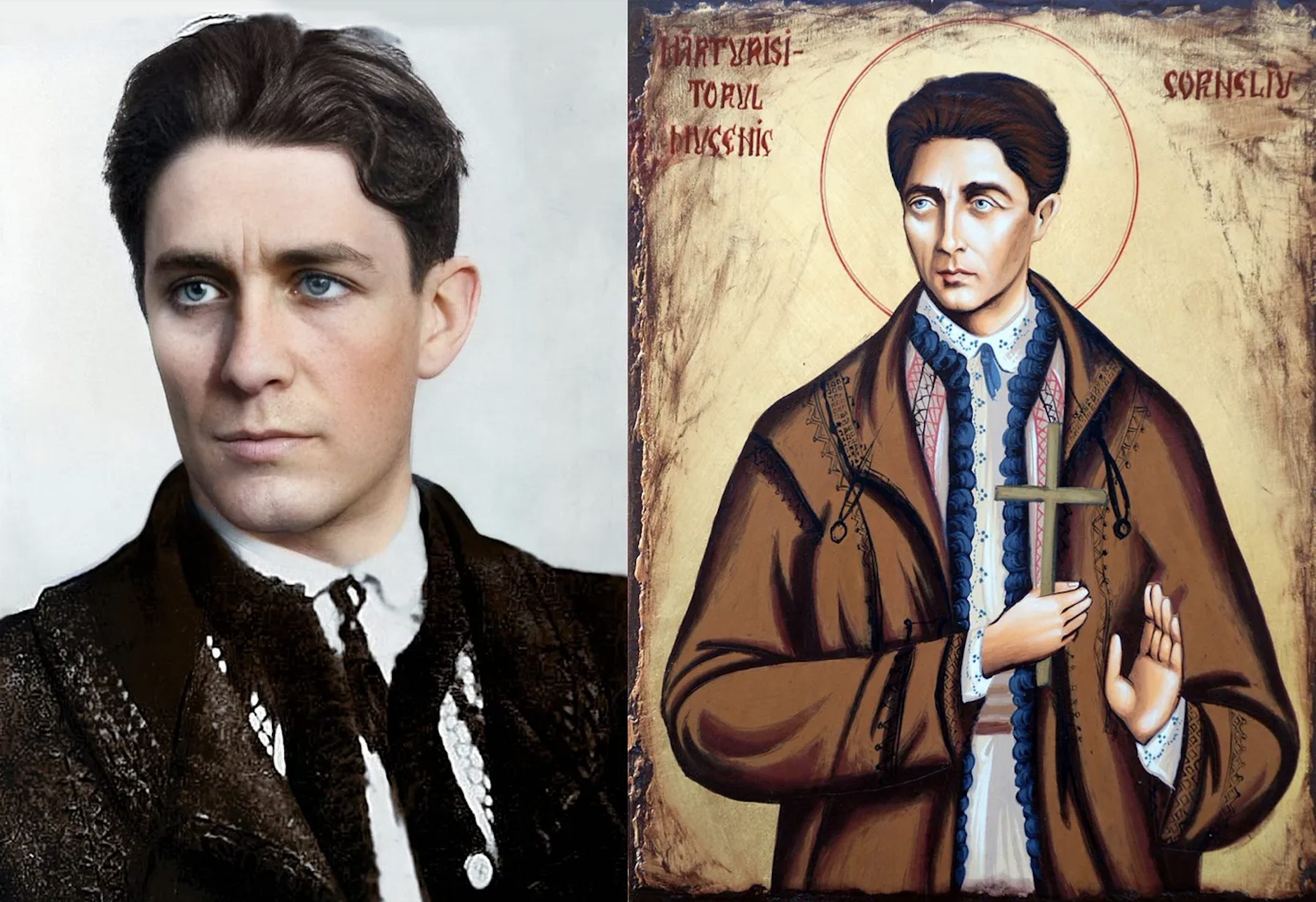

Romanian nationalism took a radical turn into the 1930s with the rise of the Iron Guard, also known as the legion of the Archangel Michael. This movement originated in the previously nominated city of Iasi, capital of Romanian nationalism, where historically resistance to Russian influence and attempts to eradicate Romanian identity was the strongest. The Iron Guard blended ultra-nationalism, Orthodox mysticism, and virulent antisemitism. Led by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, the Iron Guard saw itself as a spiritual revival of the nation, as Codreanu described it as a ‘spiritual school’ aiming to transform the Romanian soul. This ideology, later known as ‘Legionarism’ fused religious martyrdom, asceticism, and the cult of saints with nationalist ideals, portraying political struggle as a divine mission for Romanian’s spiritual and ethnic purification. The followers of this movement were called ‘Legionnaires’ who morally justified their extremist politics in religious rhetoric, carrying Orthodox icons in marches and portraying leaders as martyrs. ِAt the same time, they fomented hatred against Jews and other minorities such as Russians, Hungarians, and Romani people, whom they scapegoated for Romania’s problems and divisions during the Great Depression. The movement had a ferocious anti-communism and anti-capitalism narrative with visions of an ethnically ‘pure’ Romania.

King Carol II’s incompetence, political opportunism, and lavish lifestyle while most Romanians were threatened by famine, undermined public trust in the country’s institutions. This created a fertile ground for the rise of the Iron Guard, which soon translated its ideology into actions by taking responsibility for countless pogroms and political assassinations, such as the 1941 Bucharest pogrom, in which 100 jews were killed and slaughtered in a butchery. Soon the Iron Guard became known in Europe as the most violent antisemitic movement. The Iron Guard held power, partnering with General Ion Antonescu’s regime in 1940-41, before being suppressed after a failed rebellion. Although the movement was crushed and Codreanu killed, it maintained a long lasting legacy in Romanian politics. The movement created enduring martyrs and myths: its leader Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, was glorified by followers as a fallen prophet, often portrayed as a saint by some followers of the Romanian Orthodox Church; his grave is still a site of pilgrimage and the notion of martyred legionary who died for God and fatherland persist in Romanian memory culture and it has been used successfully in politics by anti-establishment parties such as the AUR.

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, leader of the Iron Guard, depicted as an Orthodox Saint

Suppression under Communism and Post-1989 Revival

After the war, Romania fell under the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence, which took control of Bessarabia, in what is today Moldova. The new communist rule, first under Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej and later Nicolae Ceaușescu, endorsed an official silence about the fascist past and war-time fascists leaders were executed. This repression drove fascist sympathies underground or into exile communities. Despite this repression of nationalist symbols, their legacy subtòy endured through the regime’s own brand of national-communism. Ceaușescu appropriated elements of fascist-style nationalism, Orthodox symbolism, and the myth of martyrdom, crafting a cult of personality and a narrative of Romanian exceptionalism that echoed the earlier fusion of Church nation, and sacred destiny. In doing so, the regime quietly perpetuated some ideological strands of interwar ultranationalism under a Marxist guise. During the 1989 Revolution, the latent nationalism resurfaced not just as anti-communist regime protest, but as a reclaiming of Romanian identity, allowing once-taboo symbols and narratives of interwar nationalism to reemerge in public discourse as expressions of national revival.

Romanian Revolution 1989 (Reuters)

As street battles between Romanian authorities and protesters were unfolding in the country’s major cities, protesters displayed Romanian flags and Orthodox icons, underlining the nationalist connotation of the 1989 Revolution. The victims of the Revolution began to be subject to popular veneration and were incorporated into Romania’s resistance narrative. The revolution led to the overthrowing and the execution of Nicolae Ceacescu and his wife and opened up Romania to a market economy and a pluralistic political system. Despite this, the collapse of communism left Romania in a state of deep economic disarray, marked by widespread poverty, crumbling infrastructure, and overcrowded orphanages, breeding profound disillusionment with the premises of liberal democracy and market reforms. In the 1990s two millions of Romanians left the country, and as they joined a growing diaspora and compared Romania’s poverty and dysfunction to the prosperity of Western Europe, a deep sense of national humiliation and inadequacy took root, fueling a defensive turn towards românism, an assertive nationalism that sought to reclaim dignity via ethnic pride, cultural exceptionalism,and historical myth making. This can be identified in the growing popularity of nationalist parties such as Vadim Tudor’s Greater Romania Party, which praised ethnic unity and supported the naming of streets, squares with Iron Guard ideologues, reflecting a lingering fascination with these figures. Even after the enacting of laws prohibiting fascist propaganda in 2002, veneration of members of the Iron Guard still persists, also due to the veneration of some of them by the Romanian Orthodox Church, such as Ilie Lăcătușu. This normalization of fascist symbols and figures in everyday life led to part of the population viewing them essentially as religious, patriotic, and anti establishment symbols.

Romania in the EU and NATO and the War in Ukraine

The post 1989 democratic era also brought new external influence, as Romania’s accession to NATO and the European Union meant to anchor the country in the American sphere of influence. This coincided with backlash from those who felt that traditional values and national sovereignty were under threat. Similarly to the Iron Guard’s warnings about Westernization and Judeo-Bolshevik plots, populist and far-right leaders’ discourse blends anti-globalism and anti-imperial rhetoric, depicting Brussels technocrats and cosmopolitan NGOs as foreigners attempting to dominate Romania’s affairs and to erode Romania’s Orthodox patriarchal character. The Romanian Orthodox Church placed itself as a bulwark of national identity against secular ‘European’ values and has allied itself with several far-right politicians and the AUR party. AUR party entered parliament in 2020 and casted itself as the tribune of a long-silent ‘real Romania’.

Many party members consciously appropriate the symbols and style of the interwar fascist movement and organize rallies featuring tricolor flags emblazoned with the party’s logo, mass chants of patriotic hymns, and even traditional folk costumes: images reminiscent of the legionary gatherings of the 1930s. Even the messages from the AUR is that of denunciation of corrupt elites, warning of national ‘decadence’, and invocation of an imminent national rebirth. Despite having laws that ban fascist symbols, at local levels it is still possible to find streets, squares and monuments dedicated to fascist members from the interwar period. The winner of the first round of the annulled 2024 presidential election, Calin Georgescu, publicly defined Antonescu and Codreanu as ‘heroes’ and he and other members of the AUR have publicly participated in the gatherings at the Tâncăbești cross to commemorate the ‘Capitanu’ (Codreanu).

The party’s very name invokes the ‘Unions of Romanians’ and hints at irredentist goals ofuniting all Romanians, particularly in Moldova. Its nationalist discourse has been perceived as a threat by the Hungarian minorities in Transylvania, who in the 2025 elections were urged by local leaders to stop AUR’s George Simion.

Despite being a NATO member and participating in other Western initiatives, including the construction of a new military base on the Black Sea named Mihail Kogălniceanu Air Base, Romania has become a growing target for Russian influence. This is due to several factors: lingering irredentist sentiments toward Ukraine, Romania's geographical proximity to Russian activity in the Black Sea, and a rise in Euroscepticism. While the AUR party acknowledges the threat posed by Russia, its leader, George Simion, has repeatedly stated that no other country has undermined Romanian sovereignty as much as Russia. These dynamics are closely intertwined with the broader geopolitical fallout of Russia’s war in Ukraine, which has intensified security concerns along Romania’s eastern frontier.

As a consequence of the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea and the 2022 invasion, Ukraine lost its access to the Black Sea from the Crimean peninsula and saw its access to other Black Sea ports such as Odessa and Mikholayiv restricted by frequent bombings and seamines. This forced Ukraine to invest more in the Budjak Oblast, a region right on the border between Romania and Moldova, with a sizable Romanian minority and historically contested by Bucharest. Also in this matter, the AUR has expressed irredentist claims over these areas, as well as to Snake Island and to the Ukrainians regions of Northern Bukovina and Maramures, both inhabited by Romanian minorities. Despite the AUR’s anti-Ukraine tendency, Russia’s war in Ukraine seems to have reminded Romania of Russia’s imperial threat on its Eastern border. In addition to the presence of Russian troops in the breakaway region of Transnistria, Russia’s seizure of Snake Island, a small but strategically vital outpost just 50 kilometers from Romania’s Danube Delta, effectively reestablished a Russian military foothold at Romania’s doorstep, threatening key maritime routes between the Black Sea and the Danube and jeopardizing access to the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) rich in oil and gas reserves that make Romania the EU’s largest producer of these resources.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while Romania is a member of NATO and the Three Seas Initiative, its position on the alliance’s eastern flank, alongside the persistent presence of Russian troops in Transnistria, the seizure of Snake Island, and the country’s exposure to Russian propaganda, underscores a lingering sense of vulnerability and an unresolved struggle with sovereignty. These external pressures, combined with internal insecurities, have amplified nationalist currents rooted in Romania’s historical experience of imperial domination and fascist ideology. This paper contends that Romania’s contemporary political trajectory, marked by the rise of nationalist parties and illiberal discourse, cannot be understood without acknowledging how the legacies of Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and especially Russian control, along with reimagined interwar fascist narratives, continue to shape national identity, political symbolism, and public memory. What appears today as a populist resurgence is, in truth, a reawakening of deeply embedded historical currents, and recognizing this continuity is vital not only for analyzing Romanian politics but for shaping a democratic path forward.